Electric Vehicle Batteries

Electric vehicle batteries

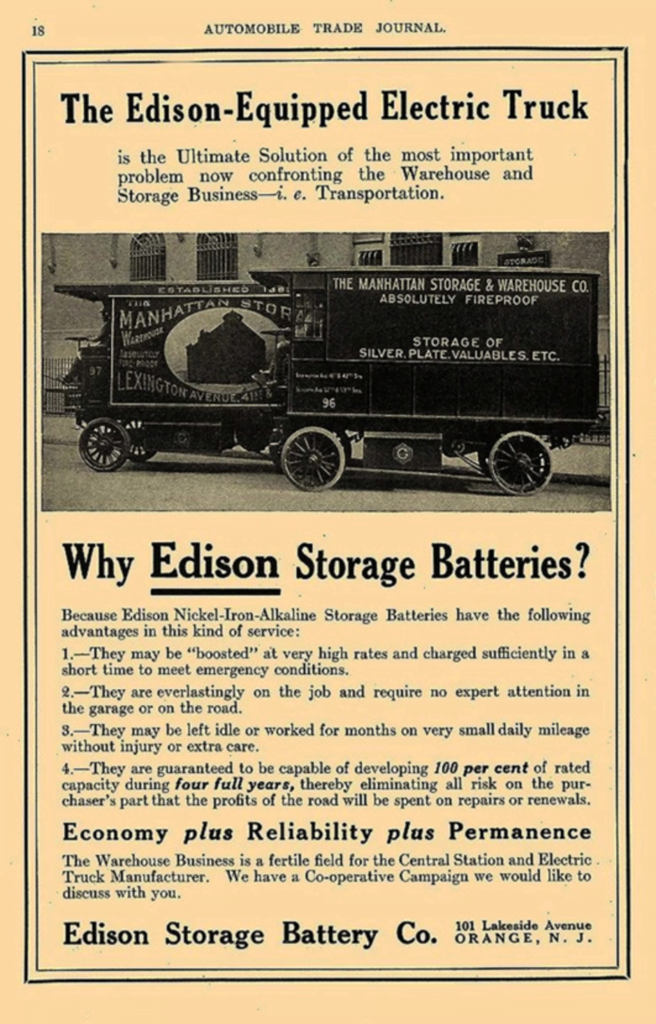

Electric vehicles were commonly used from 1880 or so. Their increased use was limited by inefficent electric vehicle batteries. This also limited speed to only 35 km/h (22 mph). Their range was about 100 km (62 mph). It also awaited adequate control technology. (See also Electric Vehicle History)

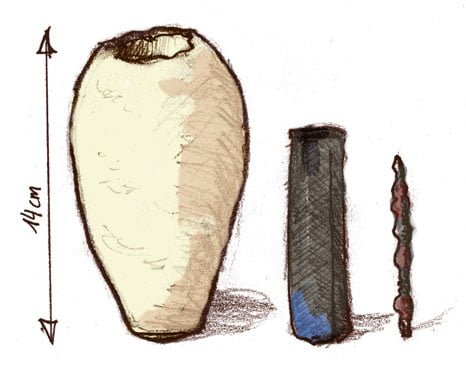

Pic: Edison Battery Archives

From 1970 onward, technology improved dramatically. AGM batteries increased driving range slightly. Otherwise, electric vehicle batteries remained almost unchanged. Most provided about 33 watt-hours per kilogram.

Nickel Hydride

In 1991, the USA launched its Advanced Battery Consortium. This resulted in the nickel hydride (NiMH) battery. This initially doubled energy – to 68 Wh/kg. That has since doubled.

Early nickel hydride (NiMH) battery. Pic: ecomento.com

While having greater energy density, NiMH’s have low charging efficiency. Moreover, they are costly. Furthermore, they tend to self-discharge. There is also hydrogen loss. Nevertheless, they still power hybrid vehicles. Honda and Toyota use them. read more…

Electric Vehicle Home Charging

Charging your electric car at home or work

Electric vehicle home charging for small electric cars is feasible at home or at work from a 15 amp power point. A power cable plugs into the car’s on-board charger. Most such vehicles have a charging unit inbuilt.

Pic: https://cleantechnica.com/

Some electric car dealers include a home charging assessment price and/or a consultation with a licensed electrical contractor as part of the car’s purchase price.

A typical electric of hybrid used for typical commuting (of 40-50 km a day) uses 2.5-5.0 kilowatt/hours. This, often called one ‘unit’, usually costs less during off-peak periods .

This guide gives some indication of how many kilometres you can drive when charging typical electric cars from a home or similar supply at their maximum rate via that inbuilt charger.

| Type: | Maximum charge (kW) | km per hour of charging |

|---|---|---|

| BMW i3 | 7.4 | 25 |

| Chevy Spark EV | 3.3 | 11 |

| Fiat 500e | 6.6 | 22 |

| Ford Focus Electric | 6.6 | 22 |

| Kia Soul EV | 6.6 | 22 |

| Mercedes B-Class Elec. | 10 | 29 |

| Mitsubishi i-MieEV | 3.3 | 11 |

| Nissan Leaf | 3.3 – 6.6 | 11 – 22 |

| Smart Electric Drive | 3.3 | 11 |

| Tesla Models S & X | 10 – 20 | 29-58 |

Charging is readily done overnight but solar captured during the day can be sold to the electricity supplier.

All electric vehicle efficiency & emissions

All Electric Vehicle Efficiency & Emissions

This article, by Collyn Rivers, discusses electric vehicle efficiency and emissions. All road vehicles emit pollution (and are health issues). Emissions are in two main forms. One includes haze and particulate matter. The other are ‘greenhouse gases’, These include carbon dioxide and methane.

Vehicle pollution – 2019. Pic: Original source unknown

Particulate matter from tyres

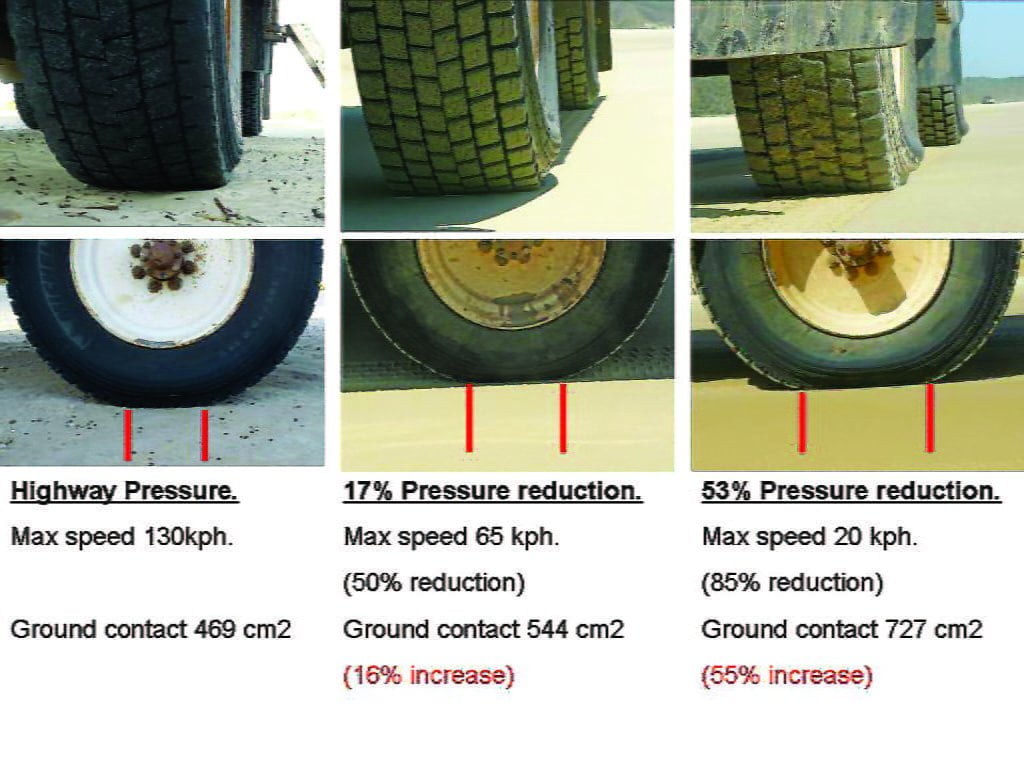

Tyres constantly shed particulate matter. It is mainly soot and styrene-butadiene. The smaller particulates are airborne. They are a minor cancer risk. https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1567725/.

The larger particles are washed into lakes and rivers etc. Related data, however, is scarce. Sweden, calculates tyre particulates as about 150 tonnes yearly. Battery-electric vehicles are heavier than those fossil-fuelled. Their tyre emissions accordingly increase.

Particulate matter from brake linings

Brake linings cause particulate emissions. These were initially asbestos cadmium, copper, lead, and zinc. All are now banned. They are now fibres of glass, steel and plastic. There are also antimony compounds, brass chips and iron filings. Also steel wool to conduct heat. These particulates disperse directly into the air. Their antimony (Sb) content may increase cancer. Most electric vehicles reduce speed by regenerative braking. This reduces brake lining emissions.

Regenerative braking

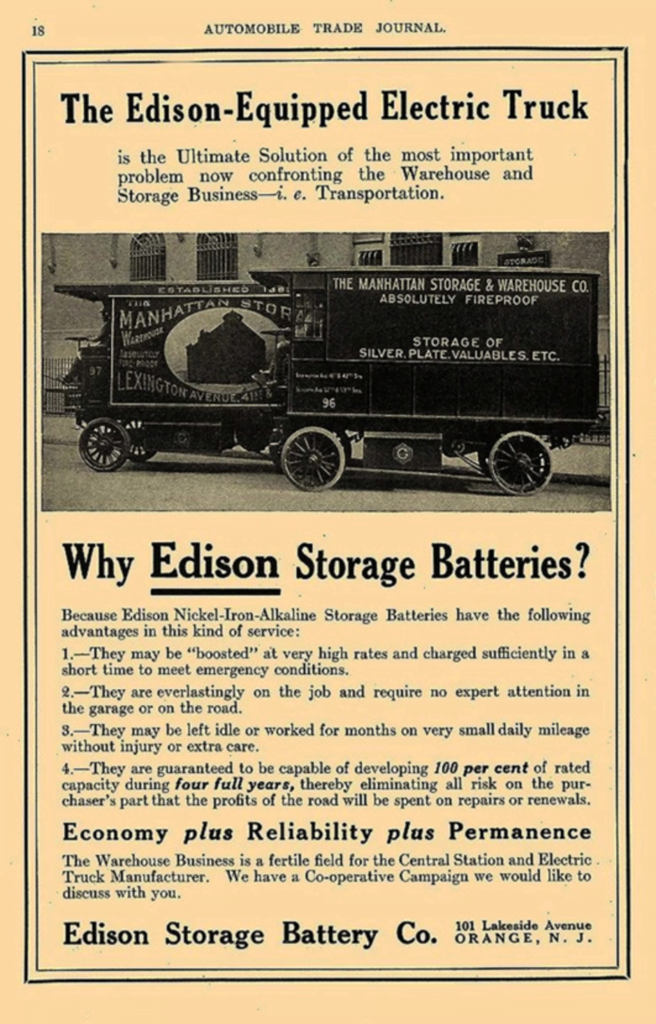

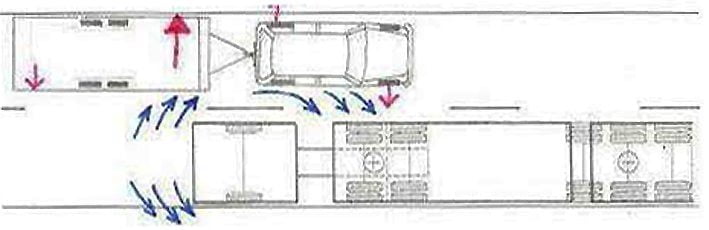

Many hybrid and most electric cars have regenerative braking. When needing to slow or stop your car’s drive motor acts as a generator. This charges the vehicle’s batteries.

Regenerative braking assists thermodynamic efficiency in all electric vehicles. Not just hybrids. It also reduces braking emissions.

Regenerative braking: whilst braking the drive motor acts as a generator, thereby charging the vehicle’s batteries. By doing so the vehicle’s kinetic energy is saved and stored for propulsive use. Pic: reworked from a concept of the Porter & Chester Institue, Connecticut, USA.

Tailpipe emissions

Electric vehicles produce negligable direct emissions. Hybrids produce no tailpipe emissions in electric mode. They have evaporative emissions, mainly during refueling. Their overall emissions are lower than those of 100% fossil-fuelled vehicles.

Indirect emissions from fossil-fuelled power stations

An Australian electricity power station. Pic: SMH.com.au.

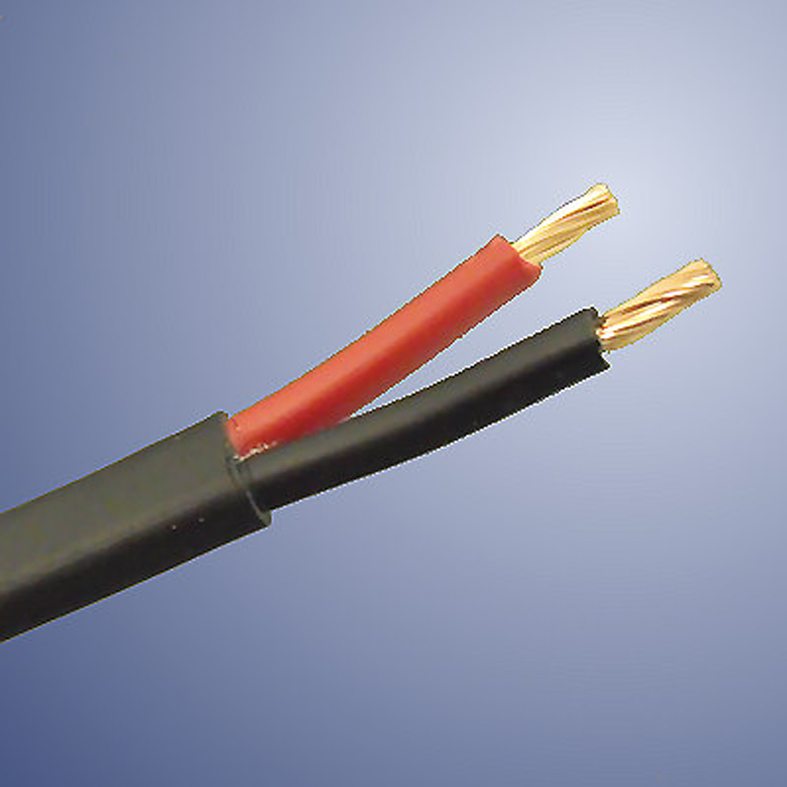

Electric vehicles run from grid power must include power station emissions. Most of Australia’s power stations are fossil-fuelled. At an averaged 920 kg CO2-per megawatt/hour, ost are below average global efficiency. None rivals China’s 670–800 kg per megawatt/hour. India has many inefficient fossil-fuelled power stations, but is the world-leader of large-scale solar power. No fossil-fuelled power station, however, converts more than 40% of heat into electricity.

Some 78% per cent of the electricity generated by Australia’s power stations is from coal. Gas accounts for just under 10%. The remaining 12% or so is from hydro, wind and solar.

Due to Australia’s power stations emissions, it seems pointless to use an electric car powered via the grid network. When battery capacity permits, however, it makes sense to go all electric. This particularly if charged via solar. Or possibly via hydrogen fuel cells.

Future power stations

Australia is unlikely to build efficient fossil-fuelled power stations. Even reducing their existing pollution is enormously costly. Their output will inevitably be undercut by renewable energy. Wind plus solar and hydro systems are cheaper and simpler. Furthermore, (once apart from manufacturing and erecting) wind, solar and hydro is pollution free.

Quantifying petrol vehicle emissions

Oil-well to vehicle emissions must include extracting, refining and distributing. Furthermore, fossil fuel powered vehicle engines are about 25% or so efficient. The remaining 75% of the energy is lost.

Overall, every litre of burned petrol causes in 3.15 kg of CO2 emissions. About 81% is caused in burning the petrol, 13% by extraction and transportation, and around 6% from refining. Burning petrol’s released nitrous oxide has 300 times the global warming potential of CO2.

A typical fossil-fuelled Australian passenger car uses about 9.0 km/litre. Driving just one kilometre generates close to 350 grams of CO2 equivalent being emitted into the atmosphere. This is about 4.8 tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions per car per year.

European disgrace

Some major European vehicle makers disgracefully concealed their diesel engine emissions. They included software that detected the vehicle’s emission were being checked. That software changed the engine’s operating mode accordingly to indicate reduced emissions.

Huge technical efforts have since been made to legimately limit fossil-fuel powered vehicle emissions. It is now, however, recognised it is not feasible to reduce them any further. This is particularly so of diesel. Reduced vehicle weight and performance assists but vehicle makers globally are now (2020) accepting their post-2030 products will be all-electric.

Current battery technology restricts range between charging. All-electric cars are fine for typical commuting to and from work. For general use right now however, hybrids make more sense.

Most cars are driven about 14,000 km/year. They emit about 4.8 tonne/year. The Toyota Prius hybrid averages just under 30 km/litre. It emits 31% CO2 (about 1.5 tonnes a year). That is 3.3 tonnes less than a comparable petrol-powered car.

Toyota Prius Hybrid. Pic: Toyota

Hydrogen

An increasing possibility is that hydrogen may replace oil as a global source of fuel. It can and is already being produced from fossil fuel. It can be done (and on a large scale) by passing an electric current through water. This now includes sea water. This enables it to be produced via both solar, wind-power and wave-power.

A so-called fuel cell enables hydrogen to be re-converted to electricity stored in so-called fuel cells. The fuel cell can then power an electric vehicle. This is not just conjecture. Many such vehicles now exist – mainly in California and Norway.

Australia’s main power stations – ages and emissions

Those known in terms of year built, and kilograms of CO2 per megawatt/hour (MWh) actually produced.

Stanwell (1996): 969 kg per MWh.

Bluewaters (2009): 982 kg per MWh.

Muja CD (1985): 982 kg per MWh.

Mt Piper (1996): 997 kg per MWh.

Collie (1999): 1004 kg per MWh.

Eraring (1982): 1011 kg per MWh.

Vales Point (1979): 1018 kg per MWh.

Callide B (1989): 1019 kg per MWh.

Bayswater (1986): 1031 kg per MWh.

Gladstone (1976): 1052 kg per MWh.

Lidell (1973): 1066 kg per MWh.

Muja AB (1969): 1285 kg per MWh.

Worsley (1982): 1324 kg per MWh.

A few of the above have now been (or soon will be) closed down.

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric vehicles.

Electric Vehicle Motors

Electric vehicle motors

AC/DC

Electric vehicle motors use one or other of the two main kinds of electricity: alternating current and direct current. Both are effective as electric vehicle motors.

Alternating Current (AC) is where electric current constantly reverses its direction. It is that used in grid power supplies. In Australia and many other countries it cycles at 50 times a second. In America it cycles at 60 times a second.

Tesla Roadster AC motor. Pic: Tesla.

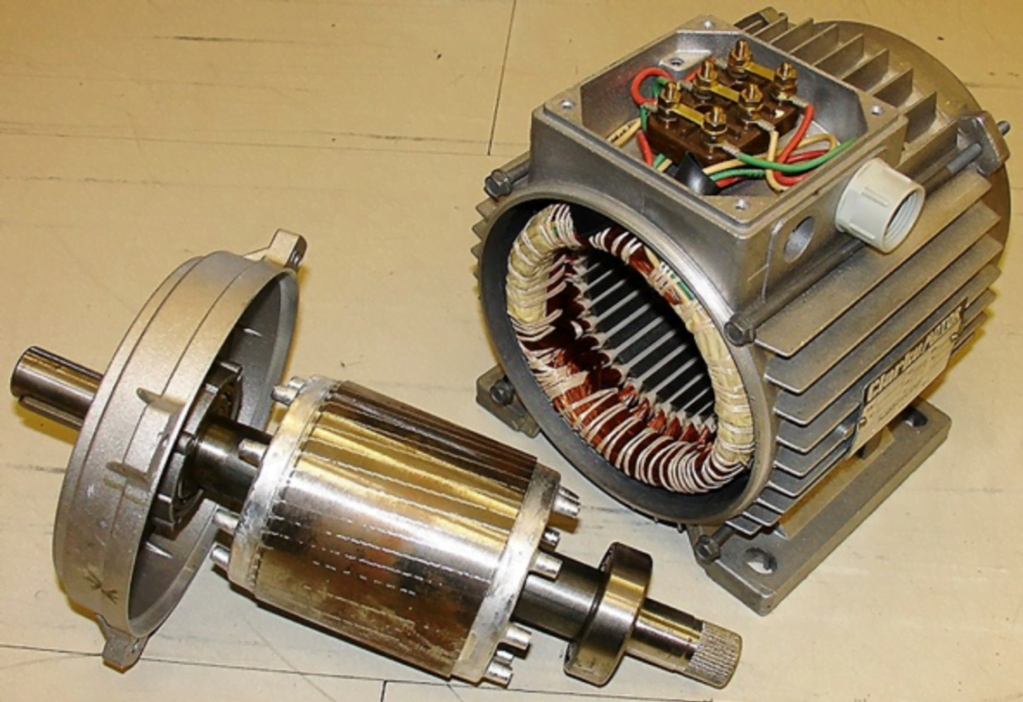

The AC induction motors used in a few electric vehicles have a stator (stationary coils of wire). When AC current flows through it, the stator generates a rotating magnetic field. That in turn causes a rotatable armature to revolve. It rotates at the rate of the AC current: i.e. at 50 or 60 times a second.

The relationship between AC voltage and its frequency enables changes in vehicle speed. The batteries’ DC output is converted to AC by an ‘inverter’. All that required is an inverter that has variable frequency. This is effective, but not that efficient.

AC induction motors are often used in hybrid vehicles. These use electric drive for limited commuting. Efficiency and range are not seen as major factors. There is however an increasing trend to direct current (DC) motors for electric vehicles.

Electric Vehicle Motors – Direct Current (DC)

Direct current (DC) is a flow of electrons in one direction. Edison is often credited as conceiving it. It was, however, initially conceived (in 1800) by Alessandro Volta. The term ‘Volt’ commorates his name.

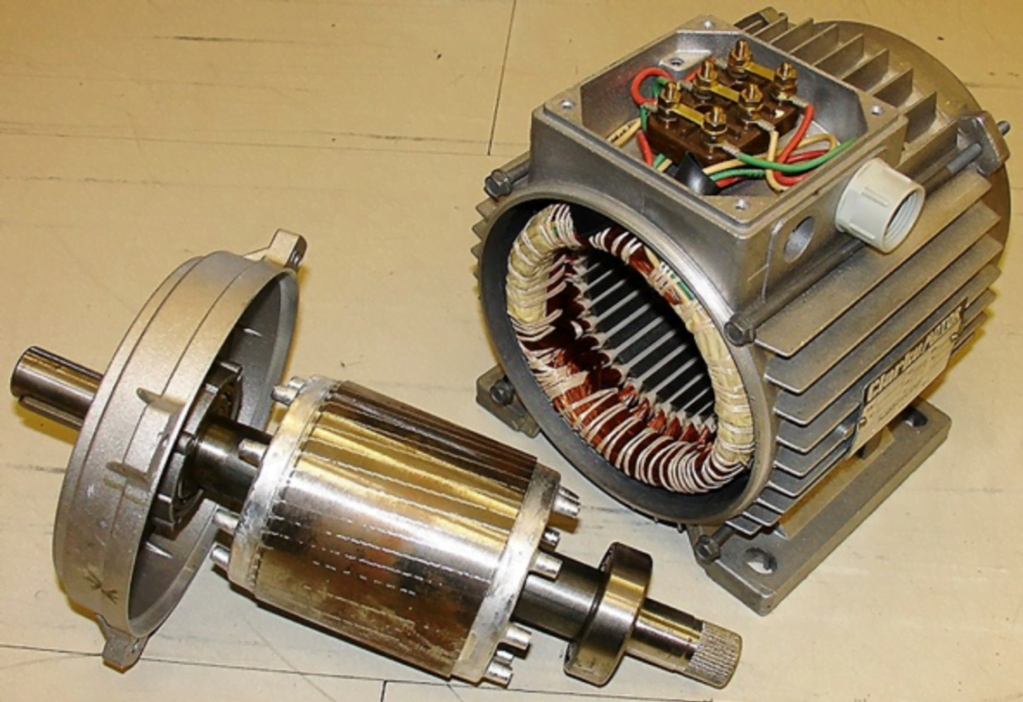

A basic DC motor has fixed external magnets. These surround a revolving armature that is an electromagnet. It also doubles as the drive shaft. Direct current is fed to this electromagnet via a commutator.

Electric Vehicle Motors – commutators & brushes

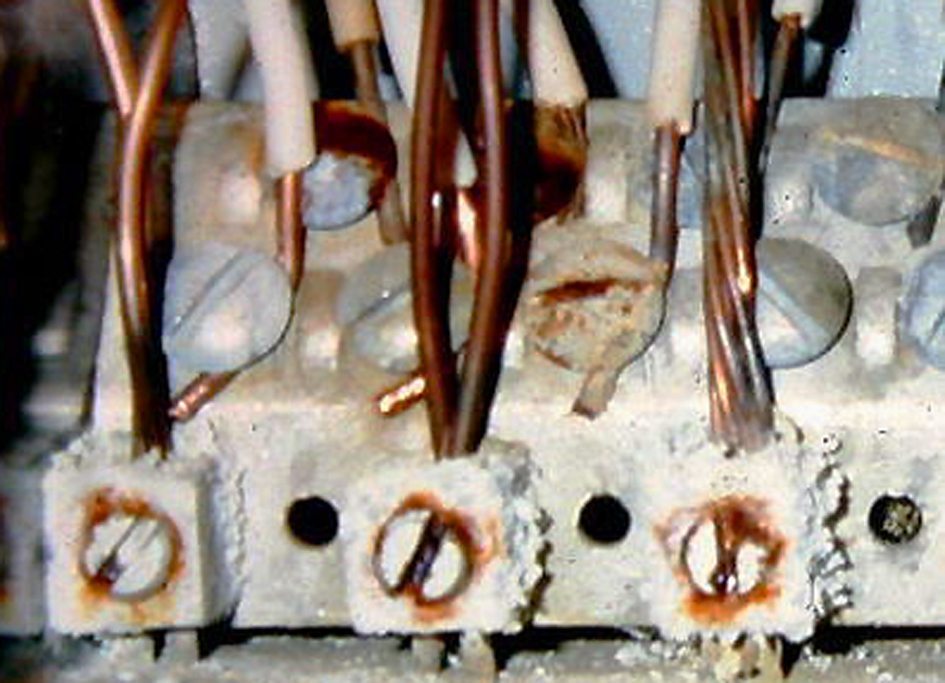

The commutator is a basic DC motor’s weak point. It is a small ‘drum’ made of an electrically-insulating material. This drum has a number of copper segments. Carbon brushes, that conduct the DC current, are sprung against these segments.

The direct current is fed to the revolving armature via those brushes. This creates a magnetic field in the armature. The magnetic field causes the armature to spin through 180 degrees. A further mechanism causes the current fed to the brushes to reverse the DC’s polarity for the second 180 degrees. And so on.

While these motors work well, the carbon brushes sprung against rotating segments, wear out. They also constantly spark. This is a potential fire hazard. Moreover, it causes electrical ‘noise’ that must be suppressed.

A few electric vehicles use basic DC motors originally designed for other purposes. There are, however, many variants that combine the benefits of both AC and DC.

A DC electric motor’s commutator. One carbon brush is attached to the yellow lead. A second (out of sight) is on the left.

Brushless DC motors

A Brushless DC motor (BLDC), is in effect a DC motor turned inside out. It has permanent magnets on the rotor that generate a rotatable magnetic field on its outside. An electronic sensor monitors the angle of the rotor. Then, via high power transistors, it applies current to generate an external electromagnetic field. That field creates a turning force.

Brushless DC motor – Pic: original source unknown

Maximum torque at zero speed

Brushless DC motors develop maximum torque at zero speed. They are efficient electrically. Moreover, they have no brushes that wear out, and no need for internal cooling. Furthermore, this enables its internal bits and pieces to be free of contamination.

These motors produce far more torque than fossil-fuelled motors of comparable size and/or weight. They can rotate at far greater speed. They are relatively light and compact. Their available power is primarily limited by heat.

BLDC motors have minor downsides. They cost more to make than their brushed counterparts. Furthermore, d at present, the permanent magnets field strength is not adjustable. Work is in progress to make it so. Once achieved that will enable increasing maximum torque at low speeds when required. This is likely to be done by using neodymium (NdFeB) magnets.

Brushless DC motors cost more than most electric motors but are nevertheless proving commercially successful. They are used for Tesla’s Model 3. It seems likely they will dominate the market.

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric vehicles.

Electric and Hybrid Vehicles

Electric Vehicle Batteries

Electric and Hybrid Vehicles

As of 2021, it is becoming increasingly clear that reducing fossil-fuelled vehicles (particularly diesel) to a truly safe level is impossible. Hence the trend to electric and hybrid vehicles. Many countries are already banning (or will ban soon) the sale of fossil-fuelled cars. These include France, Canada, Costa Rica, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and the U.K. Twelve American states adhere to California’s Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Program.

The USA’s Trump administration eased the requirement. It reduced it from the mandated 5% a year – to 1.5% a year. Environmental bodies, led by California, challenged Trump’s backward step. Unless Trump is (improbably) re-elected, this situation is likely to change.

In the first year of the current regulation, carmakers must cut emissions by 10% more than Trump required. They would then have to make 5% yearly reductions.

Administration officials say the rule would save drivers money at the pump. It would decrease fuel consumption by about 200 billion gallons over four years. Furthermore, the standards would prevent an additional 2 billion metric tonnes of carbon pollution from being released into the atmosphere.

The proposal postpones ongoing arguments over how much to restrict vehicle emissions in 2027 and beyond. In the August 2021 executive order, the President directed agencies to begin work on the next standards.

John Bozzella, CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, called on Congress and state legislatures to invest in the infrastructure needed for the increase in electric and hybrid vehicles.

In a joint statement, Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis (the merger of Fiat Chrysler and French carmaker PSA) declared their ‘shared aspiration’ to make 40% to 50% of new vehicle sales electric by the end of the decade.

Environmental advocates cheered President Biden’s administration’s pledge to cancel the Trump regulations. Many, however, say the administration’s proposed replacement does not go far enough. In a letter to the President, they called for a 60% cut to vehicle emissions by 2030. This goal would be difficult to meet under the administration’s proposed pollution rules. Furthermore, environmentalists are wary of car companies’ ongoing promises to phase out internal combustion engines. ‘Today’s proposal relies on unenforceable voluntary commitments from unreliable carmakers to make up to 50% of their fleets electric by 2030’, says Dan Becker, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s Safe Climate Transport Campaign. ‘Global warming is burning forests, roasting the West, and worsening storms. Now is not the time to propose weak standards and promise strong ones later,’ he said.

Becker and others said that auto companies already have the technology to meet tougher standards than those being proposed by the Biden administration, but rarely use it in the USA. Automakers argue they’re unable to meet stricter standards because Americans prefer larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles.

In recent years, some automakers have been able to meet federal standards. They do so, however, not by producing cleaner cars, but by cashing in credits earned by making a few electric and hybrid vehicles.

The proposed regulations are part of the administration’s efforts to push Americans to buy more electric and hybrid vehicles. Biden has asked Congress for hundreds of billions of dollars to make the vehicles more affordable through tax credits. Also to electrify 20% of the nation’s school buses by 2030.

At stake in that bill is the President’s ability to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Environmentalists say the only way to meet that goal is to mandate that all new cars be emissions-free by 2035.

So far the US federal government has announced its new rules to finalize fuel consumption and emissions standards; they’re in effect for the 2021–2026 model years. Fuel consumption and emissions must be reduced by 1.5 percent each year. The original proposal froze the standards at 2020 levels. California and other states continue to wage a lengthy legal battle to overturn all this.

Relaxed fuel-economy rules are now in effect. For new cars built over the next six years, automakers must still increase efficiency and lower carbon dioxide emissions each year but at a lower climb than the original regulations.

The new rules affect new cars and light-duty trucks from 2021 through 2026 model years. Fuel consumption and emissions must each drop by 1.5% annually as compared to the 2012 ruling’s 5% annual decreases. The 2018 draft proposal froze the 2020 model-year standards and applied them through 2026. The previous rule required an industry fleet-wide average of 54.5 mpg by the 2025 model year. This was later amended to 46.7 mpg. The final rule is 40.4 mpg. That rule ups the USA’s estimates of emissions and fuel consumption by up to two billion barrels and 923 million metric tons of CO2.

President Biden says the future of the auto industry ‘is electric and there’s no turning back. The question is whether we’ll lead or fall behind in the race for the future.’ His administration also unveiled a plan for new, stricter fuel economy and emission standards, which would be legally binding. Furthermore, they will be the most stringent such standards ever set – and followed by even stricter rules. Transportation is the USA’s largest source of greenhouse gases. Moving to electric and hybrid vehicles is seemingly the President’s central plank to fight climate change.

Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis, which make Jeep, Ram, and Chrysler vehicles, all issued statements expressing support for a 40% to 50% target of vehicle electrification. This is roughly in line with President Biden’s executive order. BMW, Honda, Volkswagen, and Volvo also said they supported it.

Currently, electric and hybrid vehicles account for about 2% of new car sales in the United States. A 40% to 50% target by 2030 is ambitious but the global auto industry has embraced electrification. Most automakers had already announced similar or more ambitious targets independently. Volvo, for instance, plans to be entirely electric by 2030.

‘These sales targets are certainly not unreasonable, and most likely achievable by 2030 given that automakers have already baked in large numbers of electric and hybrid vehicles into their future product cycles,’ noted Jessica Caldwell, an analyst at the USA car data site Edmunds. ‘Regardless of who has been in the White House, automotive industry leaders have seen the writing on the wall for some time now when it comes to electrification’.

Pic: www.drivespark.com

Apart from minor rubber tyre particles, electric vehicles are virtually emission-free. They are also about 80% efficient. If, however, their electricity is from fossil-fuelled power stations, their emissions are similar to year-2020 petrol-fuelled (or hybrid) vehicles.

Dirty Power Stations

Electricity vendors promote grid energy as ‘clean’. At present, however, that applies only to its usage. Worldwide, its generation is mostly filthy. In many countries, they generate about one–third of all carbon monoxide emissions.

Fully electrically-powered vehicles are virtually non-polluting. Most are over 80% energy efficient. If, however, the electricity they use is from most current power stations, their emissions are no lower than of a 2021 model petrol or hybrid vehicle. It thus makes little environmental sense to use an electric-only vehicle unless that electricity is wind or solar-generated. In many parts of the world is feasible (for commuting at least) to charge an electric vehicle by using solar energy at your home or place of work.

Electric and hybrid vehicles – the energy required

Most electric cars use about 1.0 kW/h to travel about 5 km. An electric vehicle (used as above) thus uses about 8 kWh of electricity/day. Grid electricity, on long-term contracts, costs about 20 cents per kW/h. If so the fuel cost is a mere A$1.60 daily. However, using grid power results in no overall fall in emissions. Unless you can solar-generate about 8 kW/h for daily commuting, it is better to use a hybrid as a typical hybrid generates less pollution than an electric-only vehicle run from our existing power stations. Hybrids, however, are being progressively being phased out globally.

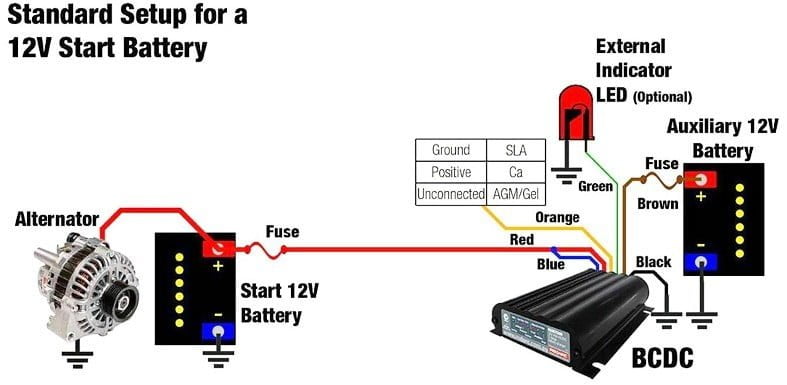

Charging from home solar

For those with ample home or business solar, it is readily feasible to charge the battery (or fuel cells) from that source. Such charging can even be done overnight by selling daytime solar energy to a grid supplier. You then repurchase it (often at low off-peak rates) at night. Or, to have ample solar energy available where the vehicle is parked during the day. Where ample sun access is available, there is a business opportunity for parking stations to provide vehicle battery charging.

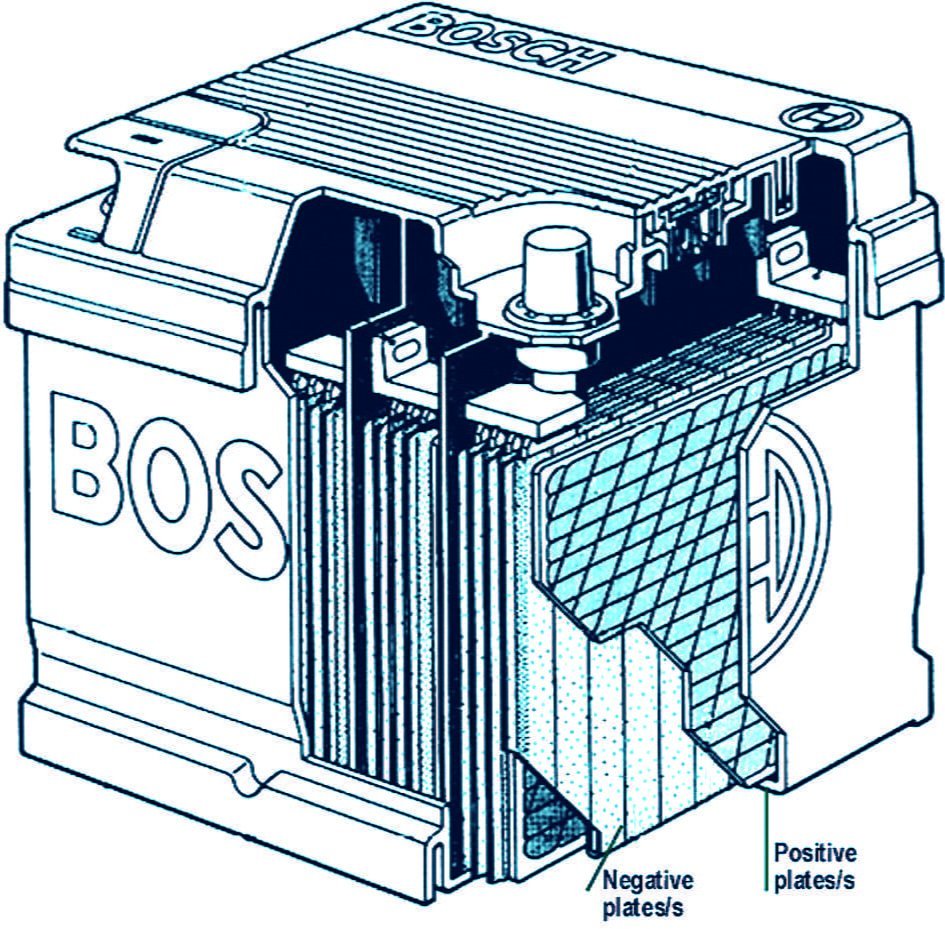

Battery Technology

Mainly retarding electric-car development is the ultra-slow improvement of rechargeable batteries. The first-known lead-acid was invented by Gaston Planté (in 1859). In 1881, Camille Alphonse Faure’s improved version (of a lead grid lattice and a lead oxide paste) enabled higher and flexible performance. It was also easier to mass-produce. Sealed versions later enabled batteries to be used in different positions without failure or leakage. That apart, there were no significant developments until the AGM (Amalgamated Glass Matt) version initially developed for the U.S. military around 1980.

The next major development was the lithium-ion battery. This reduced battery weight and volume by over three times. It enabled charging and discharging at far higher rates. But while a significant battery breakthrough, its energy storage of 0.5 MJ per kilogram is tiny. That of petrol and diesel’s is 45 M.J. per kilogram: that of hydrogen’s is 142 MJ per kilogram.

The latest major development (late-2020) is graphene-based batteries. These can (potentially) provide up to 750-800 km per full charge. Graphene is a one-atom-thick composition of carbon atoms. The atoms are tightly bound in a hexagonal or honeycomb-like structure. This virtually two-dimensional structure enables excellent electrical and thermal conductivity. It also provides high flexibility and strength, and low weight.

Graphenano claims its graphene-based batteries can be fully charged in just a few minutes. Furthermore, that they can charge and discharge 33 times faster than lithium-ion. Another development, (Gelion), uses zinc-bromine chemistry in combination with advanced electrolytes. These can be all-liquid, liquid/ion gel, or all-ion/gel.

Solid-state Batteries

Samsung’s Advanced Institute of Technology’s (SAIT) revolutionary solid-state battery may provide up to 1400 km (875 miles) range. They are about half the size of comparable batteries. The first commercial vehicles with such solid-state batteries are likely to be launched by 2025 or so.

SAIT is also studying lithium-air battery technology. It focuses on cathode technology, protective films for lithium metal anodes, and electrolytes for energy-density improvement, long-term reliability, and safety. This technology has the potential to provide a range of more than 800 km (500 miles) on a single charge.

Battery Prices

Battery prices, which were above $1,100 per kilowatt-hour in 2010, fell to $156 per kilowatt-hour in 2019. Research company BloombergNEF forecast that the average price will be close to $100/kWh by 2023.

Many other battery technologies are in hand – as are significant developments in fuel cells.

Hydrogen as a fuel

Worldwide, hydrogen is being seriously considered to replace petroleum products. A major benefit is that it is close to being emission-free. A downside, however, is that is very corrosive. In terms of mass, hydrogen has nearly three times the energy content of petrol: 120 MJ/kg versus 44 MJ/kg for petrol. In terms of volume, however, liquified hydrogen’s density is 8 MJ/L. Petrol’s density is 32 MJ/L.

Work is in progress to highly compress stored gas. Fibre-reinforced composite pressure vessels are capable of withstanding about 700 times the atmospheric pressure at a lower cost than before. Other ways include cold or cryo-compressed hydrogen storage, and materials-based hydrogen storage technologies. These include sorbents, chemical hydrogen storage materials, and metal hydrides.

Hydrogen can be used to power existing petrol-powered vehicles (and with only minor changes). Plans have already been drawn up to have fleets of hydrogen fuel-cell electric buses on routes in up to ten central hub locations across Australia.

Another approach (already by car makers) is electric vehicles fuelled by stored hydrogen that is converted to electricity by a fuel cell.

Hydrogen fuelling stations

According to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) the major hydrogen-producing states are California, Louisiana, and Texas. ‘Today, almost all of the hydrogen produced in the United States is used for refining petroleum, treating metals, producing fertilizer, and processing foods,’ the department states. However, in California, a new market for hydrogen is opening up, one driven by the demand for the gas to power fuel-cell electric vehicles. The state has been actively encouraging the growth of this market, offering carbon credits which act as an incentive to providers of hydrogen and other clean-energy technologies to establish and grow out their businesses in California.

In addition, last September, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order requiring that by 2035, all new cars and passenger trucks sold in California be zero-emission. A number of international truck manufacturing companies have already announced plans to introduce hydrogen fuel-cell powered long-haul trucks, while passenger cars fueled by hydrogen, such as the Toyota Mirai, are already on the market.

Of the 48 hydrogen fueling stations in the U.S., 45 are located in California, according to the DOE. In total, California has 50 laws and incentives related to the use of hydrogen, compared with Texas, which has seven.

Fuel cells

Fuel cell electric vehicles are fuelled by stored hydrogen that is converted to electricity by the fuel cell. They are more efficient than conventional internal combustion engine vehicles. They are almost silent. Furthermore, they produce no harmful emissions: only very pure water vapour and warm air.

These vehicles and the infrastructure to fuel them are in the early stages of being implemented. As with conventional vehicles, they take under five minutes to refuel. Currently, most have a range of about 500 km (300 miles). Fuel cell electric vehicles also have regenerative braking systems. These capture the energy lost during braking and store it in a battery.

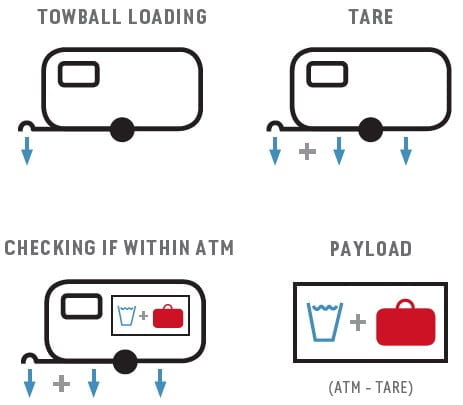

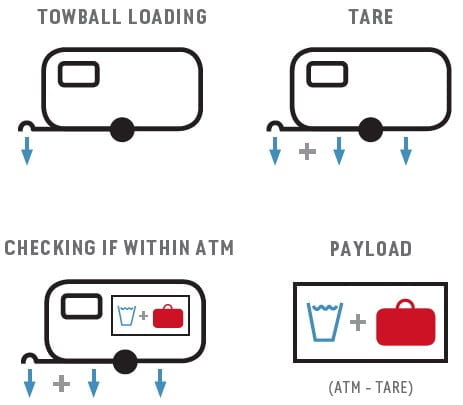

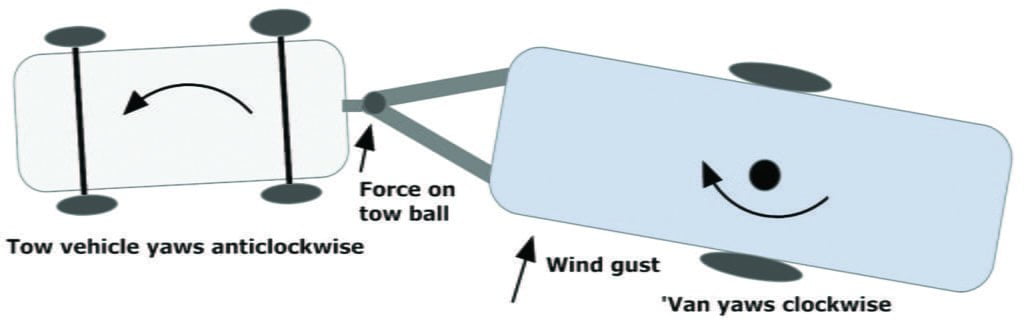

Higher Weight – a Benefit for Towing

Lighter and more energy-compact batteries are evolving. Without a truly major change in battery technology, however, vehicles suitable for caravan towing are likely to be heavier than now (late 2021). This weight, however, is a bonus. For towing stability, the tow vehicle needs to outweigh the caravan.

The secondary source of electrical energy for RV and domestic use may well be via fuel cells, of which there is significant and ongoing international development.

Electric motor drive is ideal for caravan towing

Fossil-fuelled vehicle engines only develop their maximum torque (i.e. turning power) at relatively high engine speed. The types of electric motor used in electric and hybrid vehicles, however, develop maximum torque at zero and low speed. This characteristic is ideal for caravan towing.

Electrical and hybrid vehicles suitable for caravan towing

Many hybrid SUVs and serious off-road 4WDs are available in Australia. These include the Land Rover and Range Rover, Lexus NX and R.X, the Mercedes GLE, the Mitsubishi Outlander, Nissan Pathfinder, Porsche Cayenne and Volvo X160 and X190. Also possibly worth considering are the Rivian XIT and RIS. Scheduled now for sale in 2022, each has four electric motors totalling 550 kW of power (750 hp) and 1124 Nm of torque. These enable a claimed 0-100 km/h sprint in around three seconds, with a claimed range of over 640 km (400 miles). Why anyone needs such power, however, is unclear. One U.S. magazine suggests the Rivian ‘looks like a Ford F-150 on a gym-and-yoga regime’.

Both the R1T and R1S are underpinned by the same all-electric ‘skateboard’ platform, offering up to 644 km from a 180 kWh battery pack for the dual-cab ute, and 483 km from a single charge for the seven-seat SUV.

The Toyota Land Cruiser is already being converted to an all-electric drive (for mining applications) by the Dutch company Tembo.

The Tembo Electric LandCruiser. Pic: Tembo.

According to Japan’s Best Car Web a local company is also planning to sell electric-only LandCruisers for normal use. Toyota may offer a petrol/electric hybrid Land Cruiser in Australia. The company launched one in the USA. Sales, however, did not exceed 8000 or so. The iconic Jeep Wrangler is to be sold in a hybrid form – probably by 2022. Full details have not yet been released.

The prospects for caravanners are generally good. There are seemingly no downsides apart (and initially) a need to ensure charging facilities are available in remote areas. That, however, is cheaper and simpler than for petrol or diesel. It also offers opportunities for landowners to build solar arrays and install rapid chargers

Feasible from solar

For those with ample home or business solar, it is readily feasible to charge the battery (or fuel cells) from solar. Such charging of electric and hybrid vehicles can even be done overnight by selling daytime solar energy to a grid supplier and repurchasing it (often at low agreed-off-peak rates) at night. Or, to have ample solar energy where the car is during the day.

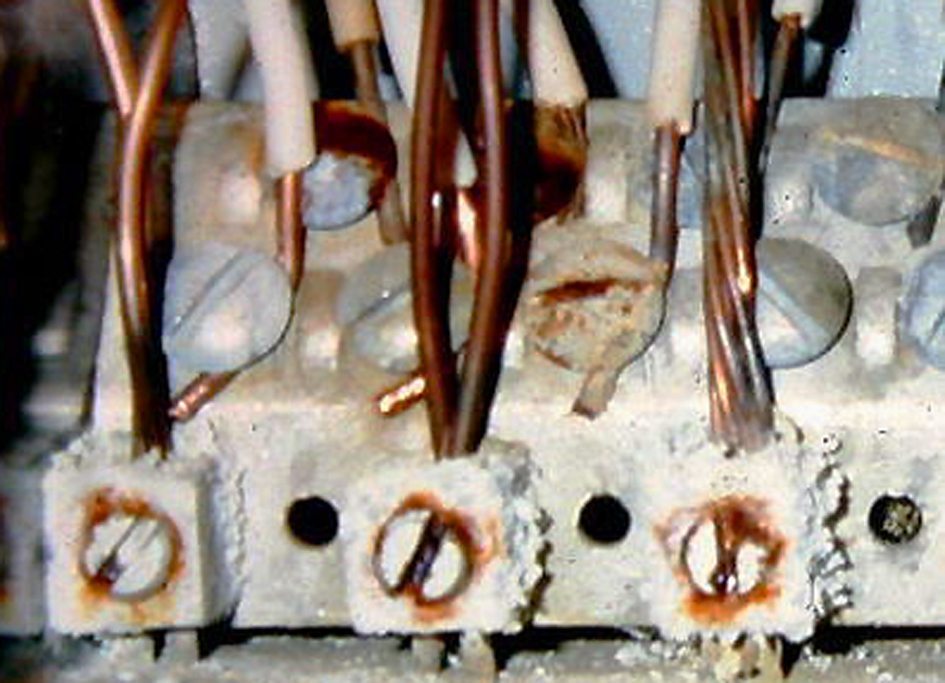

Electric vehicle charging

The cable, usually supplied with the vehicle, plugs into a 10-15 amp, single-phase power point. This, however, will provide only 10-15 km of range per hour that you’re plugged in. Not recommended if you want to fully charge your vehicle in a hurry.

That which is really required is a commonly called ‘fast charger. This needs from 25 kW to 35 kW (40–50 amp, three-phase). These are typically found in commercial premises, car parks and a few road-side locations. If at home, consult an electrician to see if it is feasible. It generally is, but will need specialised installation.

Once plugged in, the home installation will provide about 150 km of range per hour plugged in; the upper end can give you a full recharge in as little as 10 to 15 minutes.

A public AC charging point at a shopping centre or car park and a standard domestic AC “wall box” charger (which can be powered by renewable energy, like solar) you’d have at home are capable of charging at a rate of up to 7 kW (10-15 amp, single-phase). You can expect to gain around 40 km of range per hour plugged in, which will most likely be enough to top up your average daily use, and capable of fully charging your electric vehicle overnight.

How many electric car charging stations are there in Australia? At this stage, there’s not a whole lot spread across the map: approximately 2500, which is a drop in the ocean when you consider that China has 800,000-plus public EV chargers, having rolled out a whopping 4000 a day in December 2020 alone.

There are several EV charging infrastructure providers operating within Australia, including Chargefox (currently our biggest network), Jet Charge, Tritium, EVSE, Schneider Electric, Keba, EVERTY, NHP Electrical Engineering and eGo Dock.

In terms of where are the chargers within Australia, here’s a brief breakdown based on statistics gathered in October 2020.

NSW

153 DC chargers and 630 AC chargers for a combined total of 783 charging points (as you’d expect, the majority of these are in and around Sydney). There are approximately 4627 EVs in NSW, meaning there are only 0.17 charging stations per EV.

Victoria

86 DC chargers and 450 AC chargers for a combined total of 536 charging points. According to EV charging network provider Chargefox, an EV charging station located in the inner Melbourne suburb of Brunswick is the country’s busiest, with 725 charging sessions alone for the month of March, 2021.

QLD

Has 59 DC chargers and 336 AC chargers for a combined total of 395 charging points. Queensland also has what they call an “electric super highway” consisting of 31 fast-charging sites, allowing Queenslanders and tourists to confidently travel from Coolangatta to Port Douglas, and from Brisbane to Toowoomba in EVs.

WA

Has 25 DC chargers and 202 AC chargers for a combined total of 227 charging points. In April 2021, motoring organisation RAC Western Australia opened Perth’s first ultra-rapid charging station at its head office in West Perth, with chargers available offering 400km of range in less than 15 minutes.

SA

19 DC chargers and 216 AC chargers for a combined total of 235 charging points.

NT

Zero DC chargers and 13 AC chargers for a combined total of 13 charging points. No, that’s not a lot.

ACT

11 DC chargers and 39 AC chargers for a combined total of 50 charging points.

Tasmania

4 DC chargers and 64 AC chargers for a combined total of 68 charging points.

The future of EV charging stations in Australia

The adoption of EVs in Australia has been slow, hence a relatively low number of public EV charging stations, but the situation is improving.

There’s been an increase in federal and state governments investing in public chargers, and private companies have been building networks along highways.

Local councils are also increasingly installing chargers in public areas as demand for EV chargers from local communities increases.

In the Australian government’s Infrastructure Priority List 2022-23 (a guide to the investments required to ‘secure a sustainable and prosperous future’) – the independent advisory body (Infrastructure Australia) identified the development of a fast-charging network for electric cars as one of Australia’s highest national priorities over the next five years. Infrastructure Australia, however, cited a lack of access to charging stations as a major hindrance to the uptake of electric cars.

Furthermore, data from the Electric Vehicle Council of Australia (EVC) states that Australia currently has less than 2000 public charging stations and only 250 of those are fast-charging stations. The EVC likewise cites the lack of charging stations in Australia as hindering the uptake of electric and hybrid vehicles. Moreover, data shows that two-thirds of drivers still regard the lack of sufficient charging stations as a major barrier to buying an electric vehicle.

(Those currently existing in late 2020 are listed at https://myelectriccar.com.au/charge-stations-in-australia/red)

But what exactly is an electric car charging station? And are there electric car charging stations in Australia?

Different types of electric car recharge station

When it comes to categorising EV chargers, there are three different levels.

The bog-standard wall socket you plug your toaster and mobile phone charger into that delivers AC electricity? That’s a Level 1 charger.

A cable usually supplied with the EV plugs into the 10-15 amp, single-phase power point, delivering around 10-20 km of range for each hour that you’re plugged in. Not recommended if you want to fully charge your EV in a hurry.

Level 2

A public AC charging point at a shopping centre or car park and a standard domestic AC “wall box” charger (which can be powered by renewable energy, like solar) you’d have at home are both Level 2, and these dedicated EV chargers are capable of charging at a rate of up to 7 kW (10-15 amp, single-phase).

Expect to gain around 40 km of range per hour plugged in, which will most likely be enough to top up your average daily use, and capable of fully charging your EV overnight.

Level 3

Commonly called “fast chargers” or “superchargers”, these are dedicated DC chargers that operate at power levels from 25 kW to 350 kW (40–500 amp, three-phase).

As you’d guess, DC chargers deliver electricity a whole lot faster than AC chargers, and they are typically found in commercial premises, car parks, and roadside locations.

Once plugged in, the lower end of this method will add about 150 km of range per hour plugged in; the upper end can give you a full recharge in as little as 10 to 15 minutes.

Tesla has its own network of DC Superchargers in Australia – there are close to 40 spread around the country, with more on the way – but despite being the world’s fastest chargers, they’ll only work with Teslas and no other EV models.

Electric car charging stations in Australia

As of late 2021, Australia has less than 2500 public car charging stations. proximately 2500, which is a drop in the ocean when you consider that China has 800,000-plus public EV chargers, having rolled out a whopping 4000 a day in December 2020 alone.

There are several EV charging infrastructure providers operating within Australia, including Chargefox (currently our biggest network), Jet Charge, Tritium, EVSE, Schneider Electric, Keba, EVERTY, NHP Electrical Engineering and eGo Dock.

In terms of where are the chargers within Australia, here’s a brief breakdown based on statistics gathered in later 2020.

NSW

153 DC chargers and 630 AC chargers for a combined total of 783 charging points (as you’d expect, the majority of these are in and around Sydney). There are approximately 4627 EVs in NSW, meaning there are only 0.17 charging stations per EV.

Victoria

86 DC chargers and 450 AC chargers for a combined total of 536 charging points. According to EV charging network provider Chargefox, an EV charging station located in the inner Melbourne suburb of Brunswick is the country’s busiest, with 725 charging sessions alone for the month of March, 2021.

QLD

Has 59 DC chargers and 336 AC chargers for a combined total of 395 charging points. Queensland also has what they call an “electric super highway” consisting of 31 fast-charging sites, allowing Queenslanders and tourists to confidently travel from Coolangatta to Port Douglas, and from Brisbane to Toowoomba in EVs.

WA

Has 25 DC chargers and 202 AC chargers for a combined total of 227 charging points. In April 2021, motoring organisation RAC Western Australia opened Perth’s first ultra-rapid charging station at its head office in West Perth, with chargers available offering 400km of range in less than 15 minutes.

SA

19 DC chargers and 216 AC chargers for a combined total of 235 charging points.

NT

Zero DC chargers and 13 AC chargers for a combined total of 13 charging points. No, that’s not a lot.

ACT

11 DC chargers and 39 AC chargers for a combined total of 50 charging points.

Tasmania

4 DC chargers and 64 AC chargers for a combined total of 68 charging points.

The future of EV charging stations in Australia

The adoption of EVs in Australia has been slow, hence a relatively low number of public EV charging stations, but the situation is improving.

There’s been an increase in federal and state governments investing in public chargers, and private companies have been building networks along highways.

Local councils are also increasingly installing chargers in public areas as demand for EV chargers from local communities increases.

Infrastructure Australia has called for the Australian government to, over the next five years, ‘develop a network of fast-charging stations on, or in proximity to, the national highway network to provide national connectivity’: and ‘developing policies and regulation to support charging technology adoption’.

Read more about electric cars

Electric Hybrid Vehicles

Electric hybrid vehicle

Electric hybrid vehicles are powered by either or both electricity and fossil fuel. They are far from new. In 1898, Ferdinand Porsche developed a hybrid car (the Lohner-Porsche). Its petrol engine ran a generator powering electric motors in its front wheels. The car had a range of 60 km (about 37 miles) from batteries alone.

The 1898 Lohner-Porsche- the first hybrid car. Pic: Original source not known.

In 1905, American H. Piper applied for a patent for a petrol-electric hybrid vehicle. It was claimed to reach 40 km/h (25 mph) in ten seconds. The patent took a long time before granting. By the time it was, petrol-fuelled vehicles achieved similar performance.

Woods Motor Company Dual Power

The best-known early hybrid is the Woods Dual Power Model 44 Coupe. It was made from 1917-1918. The vehicle had four-cylinder 10.5 kW petrol engine. This coupled to an electric motor. The motor was powered by 115 Ah lead-acid batteries. Below 24 km/h (15 mph) the car ran from electricity. Above that, the petrol engine took over. Maximum speed was about 55 km/h (34 mph). Much like today’s hybrid cars, it had regenerative braking. Reversing was by causing the electric motor to run backwards.

The Woods petrol-electric hybrid. Pic: courtesy of Petersen Automotive Museum Archives

The Woods car was promoted as having unlimited mileage, adequate speed and great economy. Also that it was faster than most electric cars. It was very costly. Only a few hundred were sold.

The first era of electric cars was ending. Whilst quieter, none could compete with Ford’s petrol Model T. Furthermore, battery development was static. Moreover, there was thus little incentive to develop electric motive power.

Hybrid revival

Hybrid development re-arose in the USA and Japan. Due to increasing air pollution, in 1966 the U.S. Congress recommended electric-powered vehicles. One (in 1969) was General Motors’ experimental hybrid. It used electric power to 16 km/h (10 mph). It then used electric and petrol power until 21 km/h (about 13 mph). From thereon it ran on petrol. Its maximum speed was about 65 km/h (about 40 mph).

The Arab oil embargo (1973) increased interest in electric powered vehicles. One result was Volkswagen’s experimental petrol/ battery hybrid. It was not, however, mass-produced. Another was the US Postal Service trialled battery-powered vans.

In 1976, the USA encouraged developing hybrid-electric components. Furthermore,Toyota built its first (experimental) hybrid. It used a gas-turbine generator to power an electric motor.

In 1980, lawn-mower maker Briggs and Stratton developed a hybrid car. It was driven by a twin cylinder 6 kW engine. It ran on ethanol, an electric motor, or both. Twin rear wheels bore 500 kg of batteries. It could travel 50 to 110 km (31-70 miles) in electric mode, and about 320 km in hybrid. The car was a promotion for the maker’s lawn-mowers. To put it mildly, its adverse power/weight limited performance. Its reported time to reach 80 km/h (50 mph) in combined mode was 35 seconds. By comparison, even today’s slowest cars need only a few seconds.

The Briggs and Stratton hybrid. Impressive visually –but seriously underpowered.

The Briggs and Stratton hybrid. Impressive visually –but seriously underpowered.

A battery boost

A major boost for hybrid vehicles was the USA’s (1991) ‘Advanced Battery Consortium’. It aimed at producing a compact battery. The US$90 million cost resulted in nickel hydride batteries. These had about three times the capacity of comparable lead-acid batteries. This was still less than needed. It did, however, enable a new generation of electric vehicles. Hybrid and otherwise.

Toyota’s ‘Earth Charter’

In 1992 Toyota outlined its ‘Earth Charter’. Its intention was to develop and market vehicles with minimal emissions. Also that year, the USA sought low emission cars. The aim was fuel usage under 3.0 litres/100 km. Three prototypes (all hybrids) resulted. For likely political reasons, Toyota was formally excluded.

That decision back-fired. It prompted Toyota to create the Prius. That car initially went on sale, in Japan, in December 1997.

The original (1997) model NHW10 Toyota Prius. This initial model was sold only in Japan. Some, however, were imported privately into many countries. Pic: Original source unknown.

The initial version’s petrol engine produced 43 kW. Its electric motor produced 29.4 kW. It was powered by nickel-metal hydride batteries. Torque (at zero rpm) was 305 Nm. Later models had a larger petrol engine. It produced 53 kW and 115 Nm torque.

The car was an instant success. Some buyers waited six months for delivery. The Toyota Prius was launched in Australia in 2001.

European hybrids

In 1997, Audi mass-produced a hybrid. It was powered by a 67 kW 1.9-litre turbo-diesel engine. It also had a 21.6 kW electric motor. This was powered by a lead-acid gel battery. The car, however, failed to attract buyers.

Audi’s experience caused Europe to concentrate on reducing diesel emissions. Doing so, however, had ‘limitations’. Because their emissions fell far short of EU requirements, some makers illegally disguised the true levels.

Meanwhile, most electric and hybrid development was in the USA and Asia. Progress in Europe was initially slow. Now, however, (2020) there are many European electric and hybrids.

Owned by BMW, the first Mini hybrid had a 1.5-litre three-cylinder petrol turbo engine. Its electric motor had 65 kW of power and 165Nm of torque. It was powered by a 7.6kWh lithium battery. BMW claims it can travel to 40 km (about 25 miles) on electric power. A later version has a claimed 47 km (29.3 miles) range. Fuel economy is claimed to be 2.1 litres/100km. CO2 emissions are claimed to be 49 g/km.

Mini hybrid –the Countryman S E ALL4. Pic: https://www.mini.co.uk

BMW’s own hybrid initially used a 0.65 litre petrol engine to charge the drive battery (if needed). The car has since been replaced by an all-electric version. The 42.2 kWh battery enables a claimed range of 310 km (194 miles).

Porsche has two hybrids. The 2019 Cayenne E-Hybrid has a 3-litre turbocharged petrol engine. It is claimed to produce 250 kW and 450 Nm torque. An electric motor adds an additional 100 kW. Plus 400 Nm torque.

The Porsche Panamera 4 (hybrid) is much as the Cayenne hybrid. Its Turbo S E-Hybrid has a twin-turbo 4.0-litre V8 petrol engine. It develops over 505 kW and 850 Nm. Its claimed all-electric range is 22.5 km (14 miles). Furthermore, it is claimed to use 4.9-litre of petrol per 100 km (62 miles).

Volvo’s aim is to have either ‘mild’ hybrids, plug-in hybrids or battery electric cars by 2021. It plans to sell one million hybrids. Its V40 model will have a choice of engines, plus a rear axle-mounted electric motor.

Hybrid off-road vehicles

Hybrid drive works well off-road. The electric motor increases power. The fossil-fuelled motor extends range. Few however, meet 2020 Euro 7 emissions requirements. Fortunately, many have ample space for batteries. This eases their possibly legally required future conversion.

One example is the Lexus RX 450h. It retains its 3.5-litre V6, but has three electric motors energised by a 123 kW battery. This only marginally increases power (i.e. from 221 kW to 230 kW). It does, however, reduce fuel consumption. That claimed is from 9.6 litres/100 km (62 miles), to a commendable 5.7 litres/100 km.

Lexus 450h. Pic: Toyota

The Mitsubishi Outlander LS and Exceed have a two-litre petrol engine and twin electric motors. They can travel up to 55 km on their lithium batteries. Their claimed fuel usage is 1.7 litres per 100 km (62 miles).

Mitsubishi (2019 Outlander hybrid. Pic: MitsubisiNissan’s

The Nissan Pathfinder Hybrid is available in 2WD or 4WD. Each has a 2.5-litre cylinder supercharged petrol engine of 201 kW and 330 Nm. Its 12.3 kW electric motor is powered by lithium batteries. These are charged by the engine’s alternator, and regenerative braking. Fuel use is a claimed 8.6 litres per 100 km. The battery packs are under the forward-most part of the boot floor.

Subaru’s XV Hybrid uses a 2.0-litre, flat-four direct-injection petrol engine producing 110 kW of power (down from 115kW in the rest of the range) at 6000rpm and 196Nm of torque at 4000rpm. It has a lithium battery and electric motor to assist the petrol engine. It can be driven as electric only, electric motor assist or petrol engine only driving modes.

The Range Rover hybrid has all-new light alloy monocoque construction. It is unusual in being diesel-electric. The 2020 PHEV P400e’s combined power is 297 kW. The maker claims a range of up to 48 km (30 miles) in electric mode. Regenerative braking assists charging.

The Range Rover Evoque hybrid. Pic: landrover.com

The Land Rover is (now) much the same vehicle. It is, however, marketed as a more serious 4WD. It is, however, not necessarily cheaper. A few models (e.g. the LR4 HSE LUX) are more costly than Range Rovers.

Hybrid vehicles and emissions

When comparing emissions, fossil-fuelled power station efficiency needs taking into account. Most convert about 38% of their fuel into usable energy. Petrol burned by cars converts only 25%.

Energy is also lost in producing petrol and diesel. It is also lost in conveying electricity from power station to electric outlets. Furthermore, in charging electric (and hybrid) car batteries.

The National Transport Commission report assesses CO2 emissions intensity of passenger cars and light commercial vehicles in Australia. The data shows average CO2 emissions of all new cars sold in Australia during 2019 was 180.5 g/km. This is far higher than for new passenger vehicles in Europe. There, (using provisional European data) it was 120.4 g/km. Moreover, corresponding figures in Japan and the USA were 114.6 g/km and 145.8 g/km, respectively, in 2017. As that if latest available data, such emissions are almost certainly now even lower.

The National Transport Commission report reveals that Australia’s result is largely due to the increased popularity of dual cab utes and SUVs. These are three largest CO2 contributing vehicle segments. Furthermore, there are also few Australian government incentives for lower emissions vehicles. Moreover, Australia’s fuel prices are low compared with Europe.

In 2019 Suzuki is reported as having the lowest average emissions intensity (128 g/km). Ford is reported as having the highest (210 g/km). A Prius Hybrid emits 107 gram of CO2 per km.

Emissions: petrol versus diesel

On average, the CO2 emissions of diesel cars (127.0 g CO2/km) are now very close to those of petrol cars (127.6 g CO2/km). Moreover, that difference, of only 0.6 g CO2/km, was the lowest observed since the beginning of the monitoring. Diesel emissions, however, are more harmful. Furthermore, they are all-but impossible to reduce much further.

The majority of new SUVs registered are powered by petrol. Their average emissions are 134 g CO2/km. This is around 13 g per CO2/km higher than the average emissions of new petrol non-SUV passenger cars.

See also Electric Vehicles – Thermodynamic Efficiency & Emissions.

Solar-powered electric vehicles

If adequate solar energy is available an all-electric car is virtually non-polluting. There is a minor emission of rubber particles from the tyres. However, there is no equivalent of ‘tailpipe’ emissions.

Battery making, however, is seriously polluting. It is common to hybrid and all-electric cars – excepting that the latter have larger capacity batteries. See also Solar Charging Your Electric Car at Home.

An initially promising all-terrain electric car (the Tomcat) was designed and built in Australia in 2012. The first 100 sold out almost immediately. High manufacturing costs (and investor concerns) resulted in the company entering voluntary administration in February 2018.

The all-terrain electric Tomcat – sadly no more. Pic: Tomcat

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric hybrid vehicles.

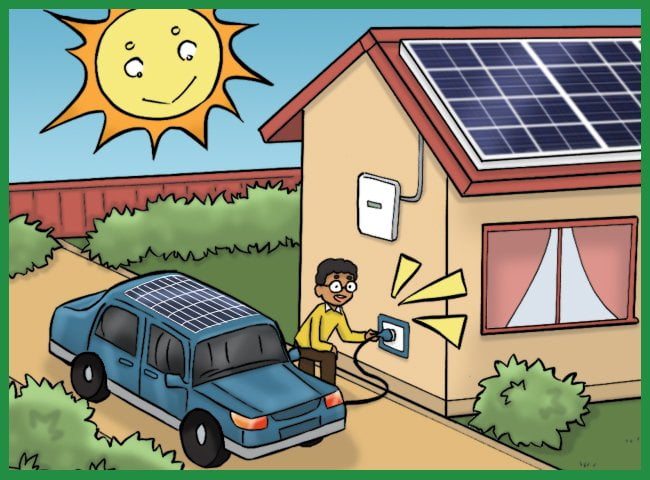

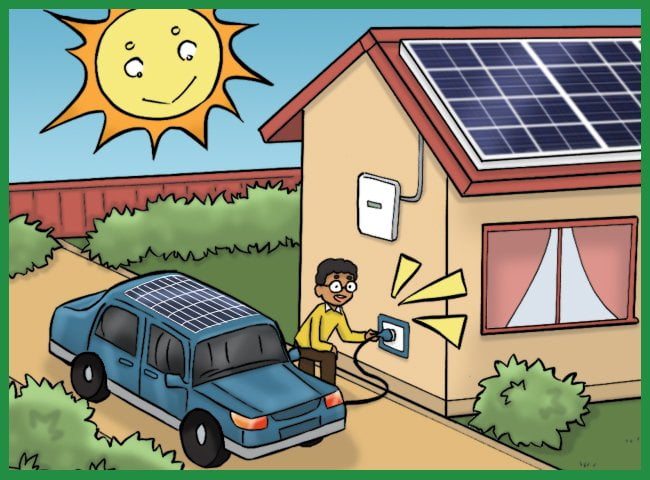

Solar charge your electric car at home

Update 2020

Solar charge your electric car at home

Solar charging your electric car at home or work is totally feasible. This article explains how. Many people already do so. Small electric cars require only a 15 amp power point. The associated cable plugs into the car’s onboard charger.

Virtually all electric vehicles have a charging unit inbuilt. Consult the vendor about charging options.

Pic: SolarQuotes

If used for commuting 40-50 km a day, re-charging requires 2.5-5 kilowatt/hours. One kilowatt hour is often called ‘one unit’. During off-peak periods it may cost less.

Here’s a guide to how many kilometres you can drive before recharging.

| Type | Maximum charge (kW) | km/hour of charging |

| BMW i3 | 7.4 | 25 |

| Chevy Spark EV | 3.3 | 11 |

| Fiat 500e | 6.6 | 22 |

| Ford Focus Electric | 6.6 | 22 |

| Kia Soul EV | 6.6 | 22 |

| Mercedes B-Class Electric | 10 | 29 |

| Mitsubishi i-MieEV | 3.3 | 11 |

| Nissan Leaf | 3.3 – 6.6 | 11 – 22 |

| Smart Electric Drive | 3.3 | 11 |

| Tesla Models S & X | 10-20 | 29-58 |

Solar charge your electric car at home – how to do it

Solar charging your electric car at home or work is feasible. Many existing grid-connect solar systems have excess capacity. You capture solar during the day and sell the excess to the electricity supplier. Then charge the car at off-peak rates at night

Most Australian suppliers ask for about 25 cents per kilowatt-hour (off-peak). That is only slightly less than buying it back off-peak. It pays to shop around. All that’s needed is a quote from one supplier. Armed with that, most existing suppliers will reduce that for a two-year contract. If not, change suppliers. Unlike most products, grid electricity is standardised.

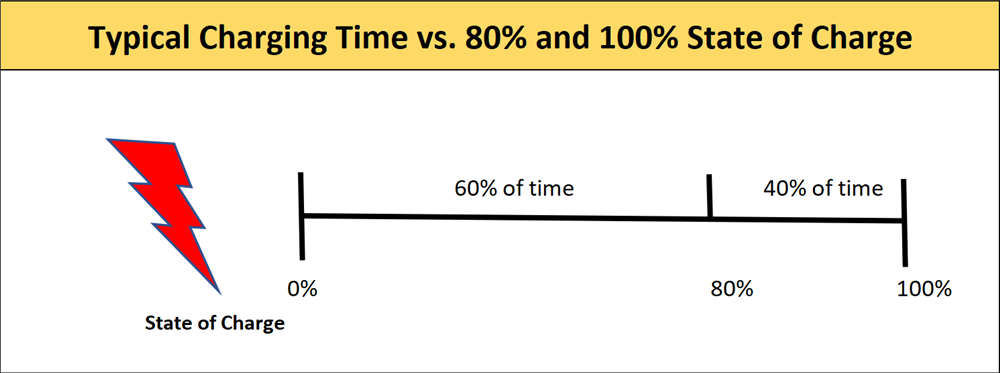

Daytime solar can be re-drawn at night to charge at off-peak rates. Many owners do this. Such charging permits charging overnight, with top-ups as required. Furthermore, it also extends battery life. All dislike ongoing deep discharging.

Using grid power costs only a dollar or two to commute. This is far less than for petrol-fuelled cars. Most use about 7 litres per 100 km. That typically costs (in 2020) about $9/day.

Economy electricity tariffs

Electric cars can be charged on economy electricity tariffs. Charging this way requires a dedicated charging point. This costs about A$1,750. A basic electric car charging unit costs about A$500. More advanced units cost up to A$2500. A licensed electrical contractor will advise re this.

If your charging rate exceeds fuse or circuit breaker rating, they must be upgraded. The cost is not high. Moreover, you save money by switching to such tariffs for charging overnight. You need, however, to install a dedicated charging point. So-using a standard electrical power point is illegal.

Another meter may be needed for the charging tariff. If so, that can be set up by your electrical contractor. Dealers may include an electrician’s advice in the car’s price.

You can reduce costs much further if you charge from a solar PV system. Furthermore, this also reduces carbon dioxide emission.

Charging at public outlets

Fast and super-fast chargers charge at up to 135 kW. They fully recharge an electric vehicle battery in 30 minutes. Owners use these only during long drives. They rely on routine charging at home and at work. Electric car vendors have charging services.

Fast charging facilities exist around Australia. They are even across the Nullabor Plain. See: Charge Stations in Australia (https://myelectriccar.com.au/charge-stations-in-australia). Or ChargePoint. Prices vary from state to state etc.

Electric Vehicle Battery Life

Battery technology is changing fast. Currently, most vehicle batteries’ life depends on their routine depth of discharge. Fully charge the batteries each night and they will live longer.

Most electric and hybrid car makers guarantee batteries for eight years. Nissan allows for 160,000 km, and capacity loss for 5 years or 96,500 km. Australians typically drive 14,000 kilometres a year. This necessitates battery replacing after about eight years. Outright failure, however, is improbable.

Summary

It is already totally feasible to charge cars from home and office solar. Moreover, it is done by many owners right now.

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric vehicles.

Electric Vehicles Energy Use

Electric vehicles energy use

Regardless of its type of fuel, the energy drawn by any road vehicle is a function of three main factors: air drag, accelerating and braking, and rolling resistance. Electric vehicles energy use is no exception.

The Tesla 3. Pic: Tesla

Air drag

This relates to frontal area and aerodynamics, and particularly to speed. The reason speed so matters is that energy use rises with the cube of the speed). It is thus also affected by driving into prevailing wind. This is not usually a major factor in most countries. It is, however, very much so on Australia’s 1675 km (141 miles) Eyre Highway. Often called the Nullarbor, the highway links South and Western Australia. It is very close to the ocean for much of the way. That wind tends to be either from in front or behind, and can be as high as 30-40 km/h. If driving into the 30 km/h wind at 90 km/h, for electric cars that’s a battery flattening equivalent 120 km/h.

Wind resistance is a powerful reason for driving anticlockwise around Australia. One drives north around September, around the top during winter, then back down the west coast and to where one started in late summer. This should result in a following wind for the west and east crossings.

Electric-only vehicles of today are most suited to urban driving. As battery technology inevitably advances, and charging facilities increase, these will be decreasing issues.

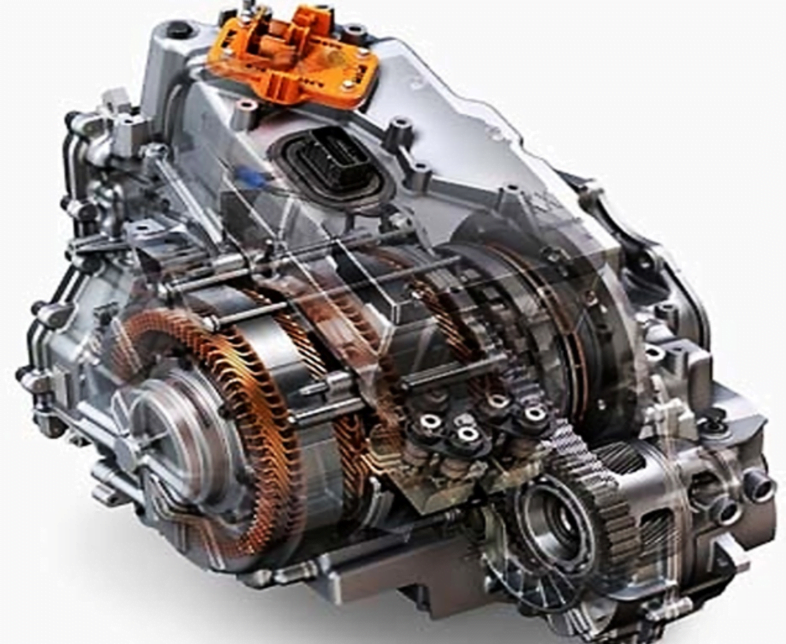

The (2016) Chevrolet Voltec electric vehicle motor and transmission. Pic: Chevrolet.

Acceleration & braking

The energy involved in acceleration and braking relates substantially to the laden weight of the vehicle. Existing batteries are far heavier than their range-equivalent petrol or diesel. An electric vehicle motor and transmission, however, is simpler and lighter. Moreover, it is also 80% to 90% efficient (a fossil-fuelled engine is only 25%).

BMW i3 ultra-light carbon-fibre body shell saves weight. Pic: BMW.

Body shells can be made much lighter: BMW’s i3 electric car has an ultra-light carbon-fibre body shell. This cancels out much of the battery weight. That extra battery weight, however, is expected to be a short-term issue. As our article Electric Vehicle Batteries notes, huge efforts are in progress worldwide to reduce the weight of rechargeable batteries. This will also enable a longer range between recharging.

Rolling resistance

Rolling resistance is directly proportional to minor friction losses, minor heat loss due to tyre wall deflection (<3%), and speed. That of fossil-fuelled,and an electric vehicle’s rolling resistance, is thus the same. There is, however, one considerable energy advantage of electric (and hybrid) vehicle over internal-combustion engined vehicles. It of simple and effective regenerative braking. This recovers the kinetic energy that would be otherwise lost in heat-generating braking. It works by an electric car’s motor momentarily acting as a generator and charging the batteries.

Stop/starting in traffic

In recent years, petrol and diesel engine cars have a (usually optional) engine stop/starting system for use in congested traffic. Whilst this saves fuel, electrical energy is used for each restart. Moreover, electric cars will have a considerable edge as no energy is drawn whilst at rest, nor extra when restarting.

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric vehicles.

Electric Vehicle History

Electric vehicle history

Electric vehicles have existed for longer than most people think. They long pre-date petrol and diesel. This electric vehicle history by Collyn Rivers is an overview.

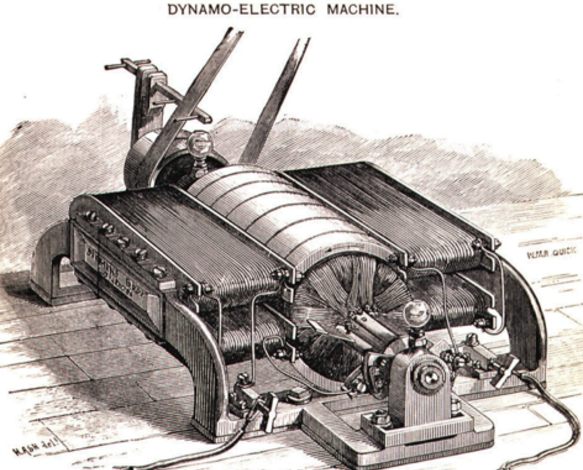

The first dc electric motor (1866). Pic: Siemens UK.

The electric battery was invented by Allessandro Volta in 1800. In 1820, Christian Oersted showed electricity could produce a magnetic field. William Sturgeon, (in 1825) invented the electromagnet. Inventors worldwide sought to build an electric motor. They used two main approaches. These were: rotating, or reciprocating (i.e. like early steam engines).

In 1834, Moritz Jacobi invented the first (realistically powerful) electric motor. By 1838 it was improved. It propelled a 14-passenger boat. Meanwhile (1835), Sibrandus Stratingh and Christopher Becker developed an electric motor. It drove a small model carriage. The first electric motor patent was granted to USA’s Thomas Davenport. Many US sources credit Davenport as ‘inventing’ the electric car. It was, however, only a small model. It had negligible power. In 1866, Werner von Siemens developed the basic DC motor. It was this that enabled the first electric cars. DC motors are used to this day.

Electric vehicles were also hampered by lack of stored energy. The only realistic source required constantly supplied diluted acid. These ‘batteries’ were like today’s fuel cells. They combined hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity. Such batteries worked. There is no record, however, of their powering electric vehicles.

The first lead-acid batteries

In 1859, Gaston Plante developed practical lead-acid batteries. They were bulky and heavy. Nevertheless, they made electric vehicles practical. Their first known usage (1897) was in New York’s electrically-powered taxis.

The first electric powered taxi – New York late 1890s. Pic: taxifarefinder.com

Electric cars’ original acceptance was thus near the end of the 1800s. Most were quieter and smoother than early petrol-fueled cars. Electric cars started instantly. They needed no ‘warming. No gear changing was required. There were even hybrids. In 1916, the Woods Motor Vehicle Company developed a car with both petrol and electrical engines. See Electric Vehicles – Hybrids.

The electric vehicle market was primarily the USA. There was, however, some usage in Europe. London had electrically-powered taxis from 1897. They became known as ‘Hummingbirds’ – due their curious sound.

A London Hummingbird electric taxi – in use from 1897 for many years. They were designed by Walter Bersey.

A London Hummingbird electric taxi – in use from 1897 for many years. They were designed by Walter Bersey.

End of an era

Electric vehicles of that era lacked adequate control technology. This limited speed to about 30 km/h (about 19 mph).

By 1920 or so, road structures (particularly the USA’s) had massively increased. This was particularly inter-city. This required a vehicle range beyond that from batteries. These, however, remained similar in weight and size as 80 years before. Moreover, recharging facilities were inadequate beyond urban areas.

Meanwhile petroleum became increasingly plentiful. This enabled it to power vehicles cheaper and further than electrically. Furthermore, mass production made them affordable. The result was Henry Ford’s (1908) mass-produced model-T. It killed sales of electric cars. Thereon, electric vehicles were used only where limited range was required. It was nearly 40 years before electric cars re-appeared.

In the late 1950s, Henney Coachworks and Exide Batteries developed an electrically-powered Renault Dauphine. It attracted some sales. It could not, however, compete in price with conventional cars. Production ceased in 1961.

General Motors EV1

In 1990 California’s Air Resources Board briefly re-ignited interest in electric cars. Its mandate required U.S. major vehicle makers to have 2% of their products totally emissions-free if used in California. This resulted in General Motors producing its EV1. It was an electric-ony car.

Early EV1s had 16.5–18.7 kWh lead-acid batteries. Later EV1s had 26.4 kWh Nickel Metal Hydride (NiMH) batteries. The car was produced from 1996 to 1999. It was the first mass-produced and purpose-designed electric vehicle of the modern era.

Usage was by leasing only. Customers liked the EV1, but General Motors saw electric vehicles as unprofitable. It sought to cease production. In 2002 EV1 usage was ceased. General Motors repossessed all of them. Most were crushed. A few were given to museums, but with deactivated motors. The Smithsonian Institution has the only intact EV1.

Major US car makers then legally questioned California’s emissions requirement. This resulted in relaxed obligations. That, in turn, enabled developing and producing low emissions vehicles. These included natural gas and hybrid engines, but not (then) electric-only.

The General Motors EV1. Pic: Wikipedia

The right concept at the wrong time

The electric car (and truck) back then was the right concept. But at the wrong time. It awaited control technology, and lighter and smaller batteries.

Control technology then improved dramatically. That of rechargeable batteries, however, did not. Moreover, the size, weight and energy stored in lead-acid batteries remained much as 100 years before.

In 1996, the University of Texas conceived the lithium battery. These store three to four times the energy as lead-acid batteries the same size and weight. They charge quickly and can release huge amounts of energy over a short time.

Now (late 2020), lithium batteries enable electric-only cars to travel 350-550 km (about 220-345 miles) between charges. This is still borderline. It is inevitable, however it is inevitable that battery technology will advance. One thousand kilometres (625 miles) is now seen as feasible. Moreover, so too are electric off-road vehicles.

Further information

It is feasible to use home and other solar (with or without grid-connect) to charge electric cars. For details on using solar to charge electric cars click here. Furthermore, articles on all aspects of electrics cars are being progressively published on this website. Moreover, these will include ongoing details of technology and charging.

The Electric Vehicle Series

This is a part of a series of articles about the history and technology involved in electric vehicles.

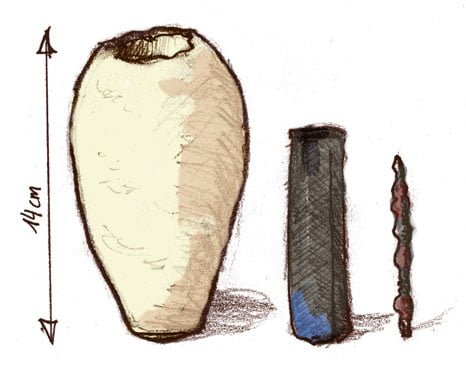

Baghdad battery myth

The Baghdad Battery

Was the battery invented over 2000 years ago? The Baghdad Battery remains controversial.

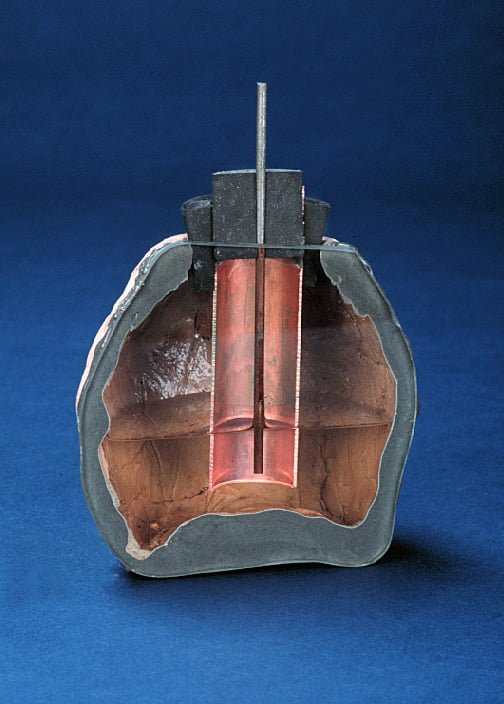

In the 1930s, German archaeologist Wilhelm Koenig was excavating an archaeological dig near Baghdad (Iraq). While doing so, he claimed to uncover a small clay jar. It had a plug that sealed the opening. That plug had a copper tube with an iron rod inserted into it. If filled with an acidic liquid, it functioned as a basic battery. Koenig and others made similar versions that generated up to two volts per unit.

Baghdad battery myth – Koenig’s paper

Koenig is variously claimed to have published a paper on the now-called ‘Baghdad battery’ in a 1938 issue of the German journal Forschungen und Fortschritte. That journal, however, ceased publication in 1967. Digitized (alleged copies) were then posted on several Internet sites. However, no evidence exists of anyone claiming to have read the original paper (if one actually existed).

A drawing of the Baghdad Battery

Koenig’s alleged paper resurfaced in the late 1960s following Erich von Däniken’s controversial book: Chariots of the Gods. This book triggered claims that ‘ancient Mesopotamians had developed batteries.’ Furthermore, that those batteries were used for everything from electroplating jewelry, to powering electric light globes inside Egypt’s pyramids and the lighthouse at Alexandria. The book also led to claims that, since the Mesopotamians did not know how to make a battery or use electricity, they must have obtained this information from someone else. Later speculation, however, suggests he read about it in a paper in the Museum’s archives.

Is the Baghdad battery a myth? – what Koenig described

Koenig described the ‘battery’ as being a flat-bottomed clay jar about 5.5 inches tall, a little over 3 inches across at its widest point, and about 1.25 inches wide at the opening. The jar’s neck was broken off, and there were bits of asphalt adhering to the inside of the rim, indicating the opening had been sealed up. Inside the jar was a hollow cylinder made from a thin sheet of copper. The cylinder’s bottom was covered by a small circle of copper sheets sealed into place by asphalt.

A severely rusted iron rod, about 3 inches long, was inside this copper cylinder. At the top end was a plug of asphalt which fitted into the opening of the copper cylinder. The iron rod projected about half an inch beyond this plug.

Koenig also describes similar clay jars found during excavations near the ancient city of Seleucia. Several clay jars of similar size were found that contained hollow copper cylinders.

These cylinders were sealed at both ends. No iron rods were found with them, but archaeologists found the remains of plant fibers, probably papyrus remnants. The cylinders were found next to a piece of bronze rod and pieces of iron wire.

One clay jar contained a small flask made only of glass. Similar remains had also been found in excavations near Baghdad.

Koenig only suggested these remnants may have been old batteries used for electroplating. He urged that further research be carried out.

This issue then became increasingly improbable. Many ‘paranormal researchers’ took Koenig’s speculation and extended it way beyond what seems reasonable. It was even suggested that technologically advanced extraterrestrials had visited the Earth in ancient times.

Most archaeological studies conclude that the ‘battery’ is simply a (decayed) papyrus scroll. Such scrolls were commonly wrapped around an iron or wooden rod and placed inside a sealed copper tube or glass flask. The now wrapped scroll was then stored inside a clay jar. The jar was then plugged with asphalt to protect it from water and weather.

Koenig’s Baghdad Battery ‘scientific paper’ is hard to take seriously. Some accounts state that Koenig excavated the battery from a site at Khujut Rabu (near Baghdad). Others, however, state that Koenig found the ‘battery’ in storage at the Museum in Baghdad.

Another account suggests the ‘battery’ was found in the ruins of a Parthian (middle Eastern) village dating from 250 BCE. Yet others classify the jar as typical of the Sassanid period – several hundred years later. It is unclear how many ‘Baghdad Batteries’ exist. Most accounts mention just one. Others, however, assert that ten or more have been found.

The object found is a flat-bottomed clay jar. It is about 5.5 inches tall, a little over 3 inches across at its widest point, and about 1.25 inches wide at the opening. The jar’s neck is broken off and has bits of asphalt adhering to the rim’s inside, indicating the opening had initially been sealed.

Inside the jar is a hollow cylinder made from a thin sheet of copper (3.8 inches long and 1 inch wide). The cylinder’s bottom is covered by a small circle of copper sheeting sealed by an asphalt coating. An iron rod (now badly rusted) about 3 inches long is held in place by an asphalt plug. The rod projects about half an inch beyond this plug.

Koenig describes similar clay jars found during excavations at Tel Omar, near the ancient city of Seleucia. Here, several clay jars of similar size were found containing hollow copper cylinders.

These cylinders, Koenig noted, had been sealed at both ends. Archaeologists later found the cylinders had remains of plant fibers, probably the remnants of papyrus. No iron rods were found with them. There were, however, a piece of bronze rod and three pieces of iron wire. One clay jar contained a small flask made of glass but no metal.

Koenig later noted that similar clay jars with copper cylinders and iron rods had been found in excavations by the Berlin Museum near Baghdad, in sites identified as Sassanid. These other finds seem to have become confused by later writers with Koenig’s ‘battery,’ thereby producing confusion about what culture and period the ‘battery’ comes from and how many were found.

Replicas of the Baghdad’ battery’ have been built by several researchers. They typically produce a small electric current (usually between 0.5 to 2.0 volts).

Koenig seems to have wrongly assumed that some ancient metal objects were electroplated – a process using mercury.

The British Museum’s Paul Craddock, however, advises that ‘examples we see from this region and era are conventional gold plating and mercury gilding.’ He states there’s no irrefutable evidence to support the electroplating theory.

Furthermore, David A. Scott, senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, states: ‘There is a natural tendency for writers dealing with chemical technology to envisage these unique ancient objects of two thousand years ago as electroplating accessories, but this is untenable, for there is absolutely no evidence for electroplating in this region at the time.’

These battery-like artifacts may have been storage for important scrolls. They need to be totally sealed. If exposed to the elements for any significant length of time, papyrus or parchment inside would completely rot away – possibly leaving a slightly acidic residue.

Professor Elizabeth Stone of Stony Brook University is an expert on Iraqi archaeology. She states that she does not know a single archaeologist who believes these artifacts were batteries.

The BBC’s MythBusters program built replica jars to see if they could have been used as batteries for electroplating or electrostimulation. One episode had 10 terracotta jars to simulate batteries using lemon juice as the electrolyte. This activated a four-volt electrochemical reaction between copper and iron plates. The show emphasized no archaeological evidence existed for connections between the jars. These are necessary to produce the required voltage for electroplating.

Koenig’s reconstruction of the ‘Battery.’ Pic: Original source unknown.

Other researchers, too, built replicas. If filled with an acidic liquid like grape juice, the ‘batteries’ produced a small electric current of between half a volt and two volts. That has led to several speculations about how the ‘batteries’ could have been used.

One is that the ‘battery’ was connected to small iron statues inside temples. If touched by a worshipper, they would produce a seemingly supernatural tingling that would show the gods’ spirits’ power.

It is known that ancient Greek temples used technological tricks to produce effects, such as doors that opened by themselves or statues that moved to awe worshippers. But there is so far no archaeological evidence that this sort of thing was done in either the Parthian or Sassanid cultures.

There are also problems with constructing the presumed battery. To function as such, it would need to be filled with an acidic liquid. This liquid would need periodic topping up, or be replaced. The jars, however, were sealed with asphalt. Moreover, the copper tube on the inside was sealed at either end. Such construction makes it hard to top up the liquid electrolyte.

The presumed ‘battery’ has no terminals and the iron rod projects beyond the asphalt plug. The copper tube, however, does not. It was thus not possible to connect wires to make an electrical circuit.

It has been suggested that such ‘batteries’ were series-connected (i.e., end to end) to produce a high enough voltage for electroplating. Electroplating, however, is done by placing the metal objects in a liquid through which an electric current is passed. Doing so deposits a thin coating of another metal onto the object.