by Collyn Rivers

Travel Trailer Design need for change

The need for travel trailer design change is increasingly necessary. Australia has two main and seemingly interdependent travel trailer industries. One makes travel trailers of stability varying from a few that are excellent, to some that should not be on the market. The other travel trailer industry makes devices (of equally varying effectiveness) intended to increase travel trailer stability. Far from all involved, however, appear to understand the basic laws of physics involved. Or they assume they are somehow immune from them.

With a few rare exceptions, there is a travel trailer design need for change. There is also a need for travel trailer owners to realise to understand, or at least accept, that a conventional travel trailer has inherent stability issues.

So-called travel trailer stability aids have fundamental limitations. An example is any form of friction-only stabiliser. The limitation here is that frictional force is a constant: the sway forces it must control, however, increase with the square of the travel trailers) speed. A sway force which might be trivial at 25 km/h is not four times greater at 100 km/h. It is sixteen times greater. One published paper (re friction-only stabilisers) states the effect of its damping at 100 km/h ‘is less than 1%’.

Known for over 500 years

The basic understanding of the mechanics and physics involved in moving objects have been known and understood for over 500 years. Despite this, some of today’s travel trailers embody principles known as unsound even back then. Around 1480, and as with today’s travel trailers, Leonardo da Vinci (in his ‘Codex Flight’) noted that ‘a body in motion desires to maintain its course in the line from which it started’.

Long travel trailers, particularly those with rear-hung spare wheels, are prone to vertical and horizontal see-saw effects. Yet Galileo (around 1600) explained in detail why and how this happens. Known technically as ‘moments along a beam’ it was raised again by Leibniz in 1684.

In 1686, Isaac Newton ‘noted that a ‘body in motion would stay in the same motion unless acted upon by another force’. Despite this basic knowledge (taught in elementary school science), many travel trailer makers and travel trailer owners seem unaware of, overlook or grossly underestimate that ‘another force’. That force can be a strong side wind-gust, strong emergency swerving etc. Or the result of seriously bad travel trailer loading.

Overhung tow hitches cause jack-knifing

Until 1920 or so, most heavy transport trailers were towed (as are today’s travel trailers) via hitches overhanging the rear of the towing vehicles. This worked well initially. Increasingly powerful engines, however, soon enabled speeds exceeding 20 mph (about 32 km/h). Jack-knifing and rollovers then became increasingly common. This was less so in the UK. Trucks there were limited to 20 mph (32 km/h) until 1957 and then to 30 mph (48 km/h) in 1957. It remained at that until 2015.

In 1920, the USA’s Fruehauf transport company realised that jack-knifing’s cause was that tow hitch overhang. That overhung hitch does not just enable a central-axled trailer to yaw. It causes it to yaw. Fruehauf accordingly located the tow hitch directly above the tow vehicles rear axle/s. Eliminating that hitch overhang solved the problem. The resultant (now-stable) so-called ‘articulated’ rigs (their hitch is often called a ‘fifth wheel’) have been used for heavy goods road transport ever since.

Many Americans then used fifth-wheel hitch travel trailers. The first known was in 1917.

The first-known recreational fifth-wheeler: the 1917 Adams motor bungalow. Pic: Glenn Curtiss Museum.

Many later fifth-wheelers were towed by modified chauffeur-driven coupes. The owner and passengers travelled in the fifth-wheeler.

The 1932 Curtiss Aerocar. The tow vehicle is a 1932 Graham-Paige. This rig was used by financier Hugh McDonald as a mobile office for his daily journey to and from New York. It had a full kitchen and bathroom. His staff included an on-board chef. Pic: HET National Automobile Museum, Steuweg, 8 NL.

Apart from the USA, most other countries opted for travel trailers towed via an overhung hitch. But right from the beginning, as in the early transport industry, jack-knifing was only too common. It was reported in early travel trailer magazines.

Travel trailer design – limiting their length

For many years the main emphasis for optimising tow vehicle and travel trailer stability has been on weight. In particular, a laden travel trailer should not weigh more than its laden tow vehicle. That was and still is important.

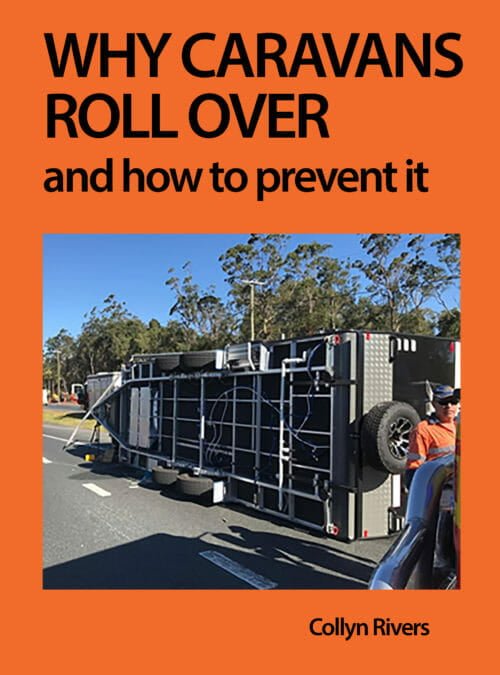

Now, however, the major limiting factor has become travel trailer length. As rollover after rollover shows, it is long twin-axled travel trailers that are now mostly involved. Many have front-located water tanks – that result in tow ball mass varying as water is used.

Many recent travel trailer rollovers are off long travel trailers with front-located water tanks

Long so-called ‘travel trailers’ are common in the USA. Most, however, towed by vehicles that are heavier and longer than used in Australia. Many are made by Airstream, a company that has long understood how to optimise trailer stability. The spare wheel, for example, is located under the chassis, to the front of the axles. Most US travel trailers use the heavy, but ultra-effective anti-sway Hensley hitch. This, in effect, uses a trapezoidal linkage that projects the virtual position of the tow ball closer to the tow vehicle’s rear axle.

Travel trailer design – the see-saw effect

A conventional travel trailer is like a see-saw. Its wheels form the pivot. As with a see-saw, the effect of weight on a travel trailer depends on how far weight is from its axle/s. An 80 kg (175 lb) adult a metre in front of the axle/s is readily balanced by a 30 kg (66 lb) child at the travel trailer‘s far end. Because of this effect, a 20 kg (44 lb) spare wheel on the rear of a seven-metre travel trailer is an effective 70 kg (155 lb) or so. Some travel trailers have two such spare wheels. If that travel trailer pitches or yaws, the effective weight of those wheels is magnified yet more. They initially strongly resist that movement, but once that (so-called inertia) is overcome, they then equally resist ceasing it.

This spare wheel ‘end-heavy’ issue is often raised on travel trailer forums. It attracts naive responses to the effect that all is fine – ‘the travel trailer has been designed accordingly’. Physics, however, does not work like that. Do some travel trailer makers not realise this? Or do they simply do not care about its inherently adverse effects?

Travel trailer stability standards

No Australian Standard currently addresses this issue. The national trailer standard, VSB1, states ‘There are no specific body structural requirements, but the trailer must be safe and fit for purpose.’ VSB1 suggests as a minimum: that the manufacturer should be able to demonstrate that the structure is capable of supporting the designed payload with a ‘safety factor of at least three for highway use and a safety factor of five for off-road use.’ It does not comment on stability. Nor do any other Australian Standards or regulations.

Nor is travel trailer stability mentioned in the travel trailer industry Association of Australia Ltd’s own RVMAP Code of Practice. It is almost entirely concerned about building the product. Page 48 of that industry’s travel trailer towing guide, shows a travel trailer that has two bicycles and a motorcycle on the rear of a travel trailer. It comments only that they obscure the number plate. This is an extraordinary sense of priority. https://caravantowingguide.com.au/pdf/TowingGuide2018.pdf

The SAE J2807 standard

Travel trailer stability is addressed in the USA’s J2807. Initiated by Toyota in 2010 this (now) SAE Standard is followed by all US and the top three Japanese vehicle makers. It sets out the performance requirements for determining tow vehicle gross combination weight rating, and trailer weight rating.

The SAE J2807 standard covers all vehicle and trailer combinations of a combined laden weight up to 5896 kg (13,000 lbs). The standard sets out tow-vehicle requirement for (combination) vehicle requirements for acceleration, hill climbing, understeer, trailer sway response and braking (at maximum legal laden weight). It also covers the tow hitch and related components. The main handling requirements relate to ‘cornering power’. It also covers the tow vehicle’s reduction inherent cornering power (of about 25%) when using a weight distributing hitch.

Factors affecting stability

A travel trailer and tow vehicle’s stability is co-dependent.

Assuming correct loading and tow ball mass, excess caravan length is now the major cause of travel trailer instability. Weight, if centralised, and not excessive, is less of an issue.

Critical speed

A reasonably stable travel trailer is likely to become unstable if its tow vehicle is lighter or much shorter. And/or that tow vehicle has too low air pressure in its rear tyres. Or the travel trailer has too low tow ball mass.

For any combination of travel trailer and tow vehicle (and their loading), there is a critical speed. That critical speed is unique to each rig. It is related to many factors. These particularly include tow ball mass and travel trailer length and loading. The lower the tow ball mass the lower that critical speed. For most Australian rigs that speed is likely to be a little over 100 km/h. For some rigs, it will be below 100 km/h.

The issue of critical speed is often misunderstood. It does not follow that the rig will become unstable at, or above that speed. If towing at or above that critical speed, however, jack-knifing is far more probable in the event of an emergency swerve (or strong side-wind gusts). There is no currently-known way of establishing a rig’s critical speed (apart from wrecking it by testing) but the risk is far less by never exceeding 100 km/h. Forum dash-cam videos show many rigs beginning to jack-knife while overtaking heavy transport vehicles. As such vehicles travel at 100 km/h wherever possible, it is all but certain that most rigs were thus well exceeding 100 km/h.

Adverse effects of a weight distributing hitch

The critical speed is lowered if a weight distributing hitch (WDH) is used. The tighter that hitch the lower that critical speed. Here’s why.

Travel trailer towing reality is that if you need a WDH, you are imposing loads on a tow vehicle neither designed nor intended to withstand such loads.

A WDH compensates only for vertical loads. It does so by moving some tow ball weight from the tow vehicle’s rear tyres to its front tyres. The WDH cannot, however, reduce the side forces on those tyres when a travel trailer yaws or starts snaking. That lessened weight reduces their ability to cope with those side forces.

That WDH also reduces the tow vehicle’s intended and vital margin of understeer (that assists keep it stable). This may prejudice its handling in emergencies. It that tow vehicle loses all understeer at speed, it oversteers. If that happens jack-knifing is all-but-inevitable.

If using a WDH never adjust it to more than 50% correction. Contrary to ongoing forum mal-advice never adjust that WDH to have the travel trailer and tow vehicle level. When correctly adjusted, the caravan’s nose weight should cause the rear of the tow vehicle to be about 50 mm lower.

ow-ball weight

As with an arrow, it is vital that a travel trailer be nose-heavy. Tow ball weight is totally related to critical speed. The lower that tow ball weight – the lower that critical speed.

Following a general (2015) reduction in tow vehicle permitted tow ball weight, many local travel trailer makers then recommended only 4% tow ball weight – yet retaining virtually the identical design for which they previously recommended 8-10%. One astute observer described this as ‘brochure engineering’.

If all else remains equal, the speed at which a towed travel trailer is likely to sway is directly related to its tow ball weight. A travel trailer with low tow ball weight may not sway in normal driving. If it does, however, jack-knifing is far more likely. Any number of academic papers backed up by real-life testing confirms this. One USA study showed that a travel trailer with 4% tow ball weight had a critical speed of only 40 mph (about 64 km/h).

Travel trailer design – how to increase your rig’s stability

When buying a tow vehicle, choose one that has the maximum wheelbase (i.e. the distance between the front and rear axle). Furthermore, the shorter the rear overhang, the better. Also, when fully laden, that tow vehicle should weigh at least as much as the fully laden caravan.

Travel trailer length too is a vital factor. The longer the caravan, the less stable it is.

Use a tow hitch with the shortest possible overhang. Avoid even excess millimetres. If necessary have a machine-shop shorten that overhang. This usually involves simply drilling a new hole. It can be owner-done – but that hole must be only just large enough to provide a tight fit for the hitch securing bolt.

Do not lubricate the tow ball – its friction assists to limit sway. AL-KO has one that deliberately increases its friction. See Should I grease a tow ball.

When towing always load the tow vehicle to its legal maximum. If the fully-laden tow vehicle weighs less than the laden travel trailer, never exceed 100 km/h. In stating this, RV Books does not imply that towing such a weight at 100 km/h is safe.

Ensure, by weighing on a certified weighbridge, that your laden travel trailer is not overweight. Ongoing police checks show that almost all are – one was reported as being 400 kg (880 lb) over its legal maximum.

Never have anything heavy at the far rear of a travel trailer. That many travel trailers have spare wheels located there is contrary to the laws of physics – not just common sense. And why two spare wheels – when tow vehicles have only one – or do not even carry a spare wheel: many have a repair kit and an inflator.

Tyre pressures matter

Tow vehicle rear tyre pressures should be increased by 50-70 kPa (7-10 psi). Never increase front tyre pressures.

For reasons unclear, many travel trailer makers recommend using the maximum tyre pressures the tyre can withstand. The Caravan Council of Australia (and RV Books), however, strongly recommend using the tyre maker’s advised pressures for the travel trailer‘s laden weight.

Friction sway control

Friction-based sway control is effective, but only at low speed. This is because frictional forces remain constant. The sway forces they seek to control, however, increase by the square of the rig’s speed. At 100 km/h that friction is a close-to-useless 1%.

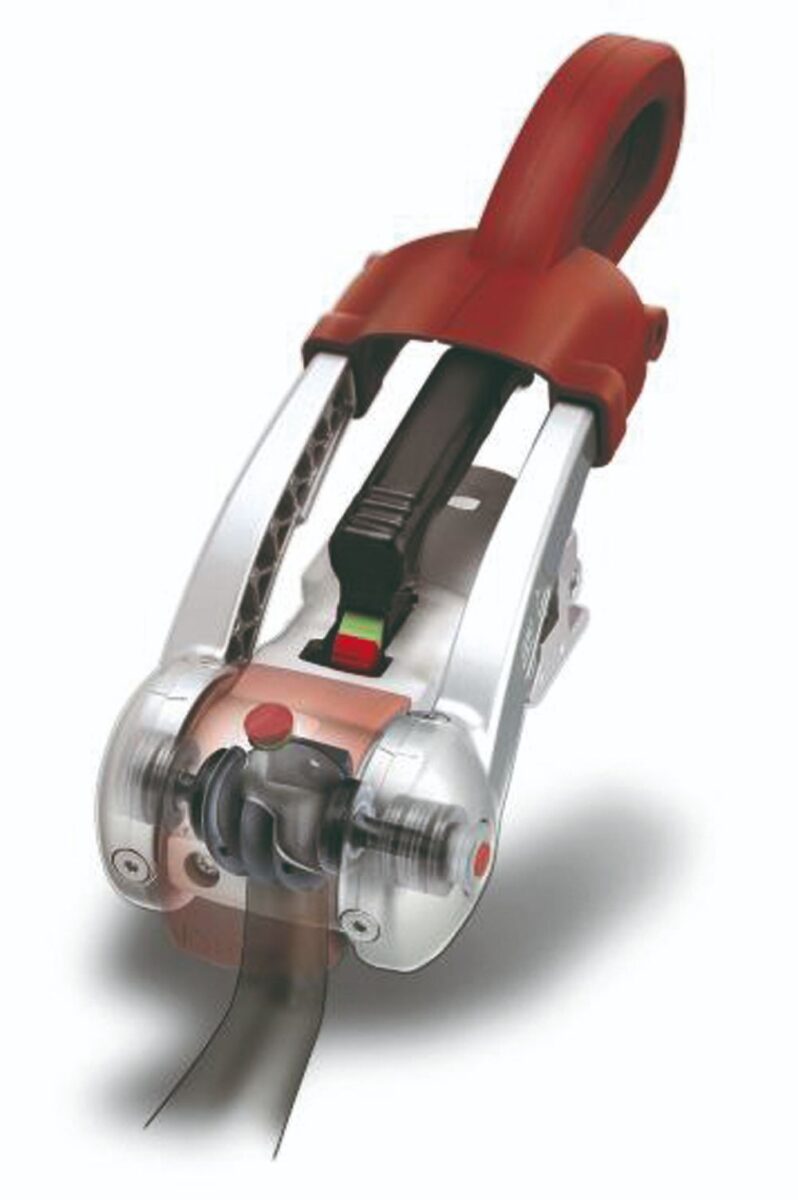

This inherent limitation is recognised in the UK and EU. There, the excellent AL-KO friction tow ball handles low to medium speed sway (yaw). Electronic stability control, however, acts (if needed) at higher speeds.

The AL-KO friction tow ball is very effective at low to medium towing speed. Pic: AL-KO UK.

Forum advice often misleads

Even good travel trailer design is rendered unstable if laden incorrectly. Here, some travel trailer forum advice seriously misleads. Travel trailers must be laden such that most of the weight (as possible) is close to (and preferably over) their axle/s. The required tow ball mass must only be achieved this way. Never adjust tow ball weight by adding sandbags etc at the very front.

Ultimately, travel trailer and tow vehicle behaviour depend on hand-sized rubber oval sections’ grip on the road. That ‘grip’ on dirt roads is on loose gravel (often corrugated). It is not unlike driving on ball bearings.

Never tow at over 100 km/h. Moreover, always bear in that travel trailer stability requires adequate tow ball weight. Furthermore, the lower that mass, the lower the speed that travel trailer is likely to sway.

That not generally realised is that it not so much travel trailer weight that matters. It is far more an issue of travel trailer length. Assuming sane loading, a two-tonne 14-foot (4.26 metres) travel trailer (some exist) is likely to be far more stable than a two-tonne 18-foot (about 5.5 metres) travel trailer.

Further information

This and associated travel trailer design issues are covered in depth in our (now top-selling book) Why Caravans Roll Over – and how to prevent it. As with all RV Books, it is available worldwide in eBook and paperback versions. They are obtainable directly from RV Books – or via outlets such as Amazon.com etc.